Sean Fullerton is a former secondary physical education teacher and current Ph.D. student at the University of New Mexico in the Health, Exercise, and Sports Science Department. In this article, Sean explores student centered learning examples in physical education with the use of technology. Be on the lookout for lots of great content from Sean as he helps take the academic angle of physical education best practices.

Student centered learning places the focal point of instruction on the individual needs of the students, rather than the teacher. Many physical educators would agree, learning in physical education (PE) should be relevant to the lives of students. Creating a student centered PE program can be done by using a few simple strategies. Let’s breakdown student centered learning examples with technology for physical education.

Aligning the Standards

Lund and Tannehill (2015) provide a multi-step approach to developing standards-based curriculum. After creating a purpose statement for the PE program, standards-based curriculum follows these steps:

1) Identify and define relevant standards.

2) Identify specific skills, knowledge, and dispositions students should demonstrate to meet the standards.

3) Identify curricular models, including the activities that will allow students to reach the outcomes stated in the standards

Aligning the student learning objectives, assessment strategies, and learning activities is known as instructional alignment (Lund & Tannehill, 2015). Curtner-Smith (1999) found that teachers will adapt, recreate, and modify national curriculum or standards to fit their personal views about teaching PE.

Unfortunately, some physical educators prioritize their personal interests and apprehensions when making curricular decisions, with little concern for student learning and outcomes (Ferry & McCaughtry, 2015). Implementation of newer curriculum and activities can be done if teachers place the students’ needs at the forefront of curriculum and instructional decisions.

Cothran (2001) found that relationships with students are critical to providing teachers with confidence in adopting and implementing new curriculum. It is important that teachers take into account the context of the larger community in which the students live to create relative learning experiences that are student-centered.

Free Professional Development For PE

From full courses to on-demand webinars, tap into the PLT4M classroom for continuing education opportunities for physical education teachers.

Student Centered Learning Examples – Student Input

Secondary physical educators’ emotions related to sports, personal identities, and experiences have been shown to directly influence the types of activities that are included in their curriculum. Teachers who have strong emotional ties to sports are more likely to emphasize those sports in their PE curriculum (Ferry & Mcoughtry, 2013). Many PE experiences are also not aligned with what students feel is important and useful (Simonton et al., 2022). One of the best ways to counter this is by considering student centered learning examples that layer in student input.

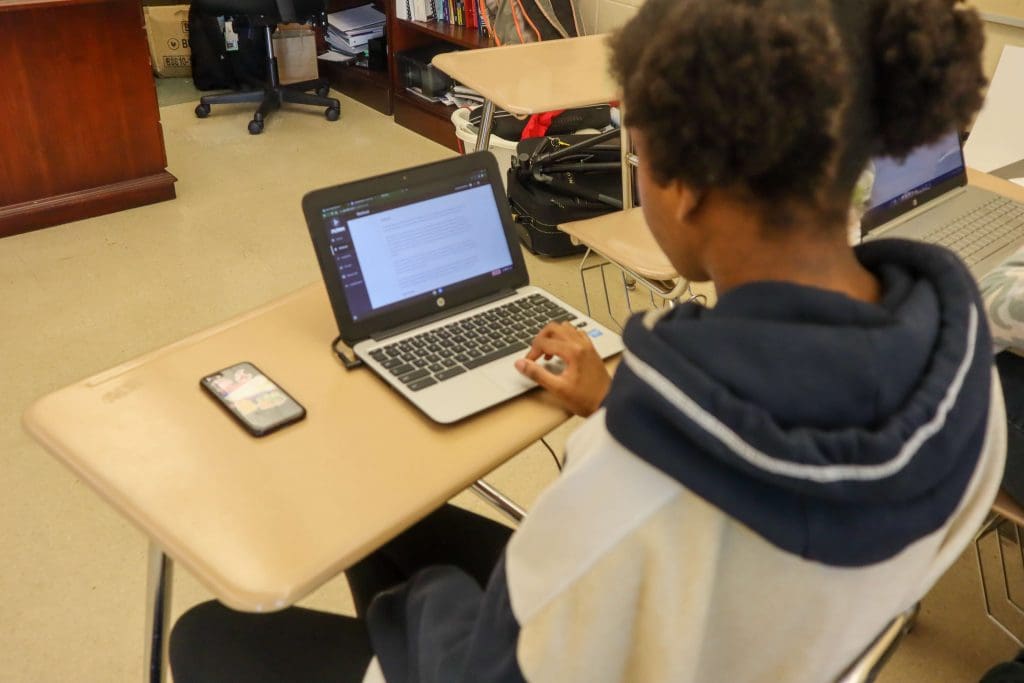

To get an idea of what students find most useful and interesting, this can be done through simple data collection strategies. Teachers can use Google Forms to deliver surveys to students about their interests, perception of current practices, and voice opinions regarding their own learning. Ison (2021) provides an example of a high school PE program in Illinois that was built with student interests in mind, creating courses that were more relevant to students’ lives than traditional course offerings.

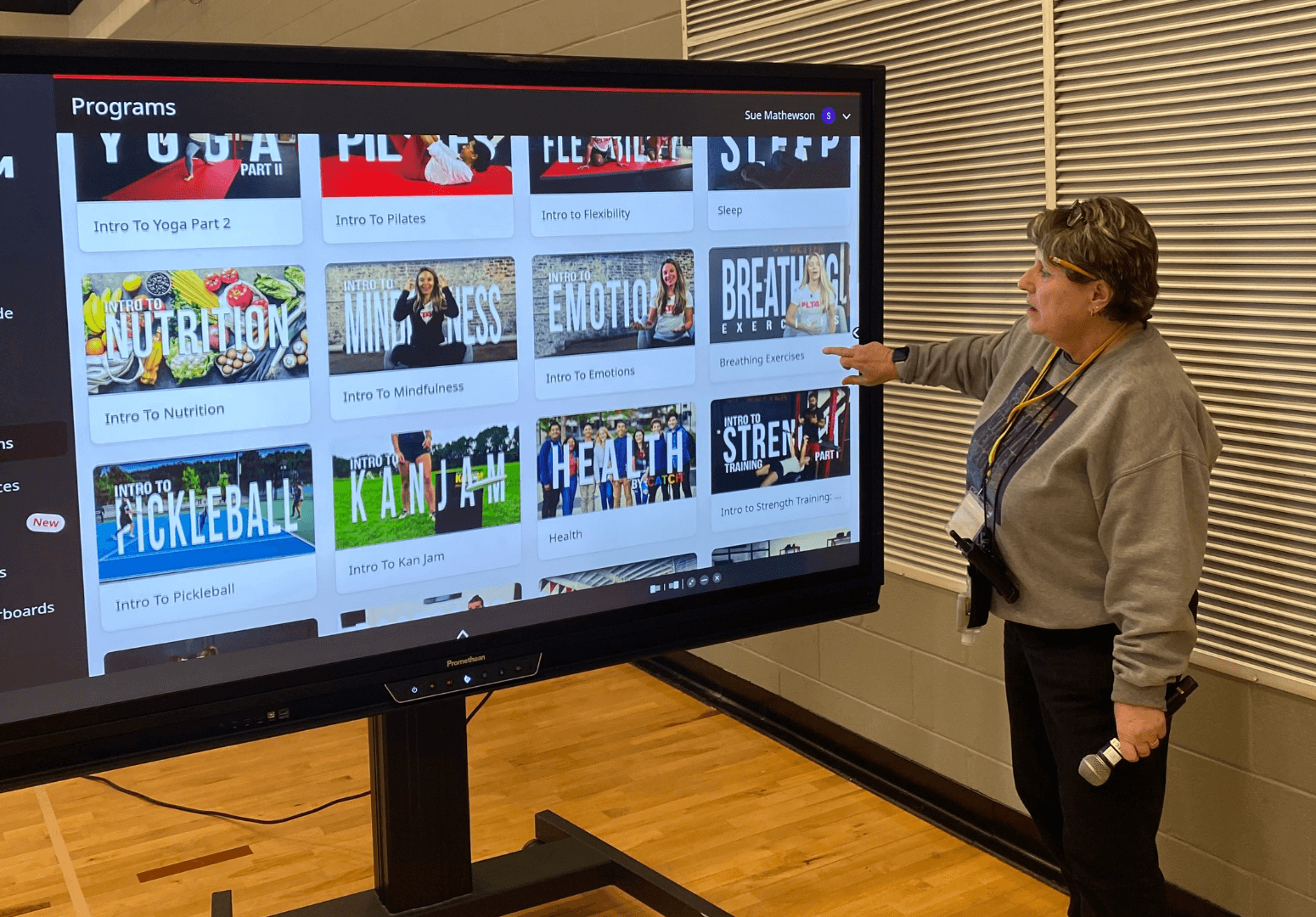

Check out other schools student centered learning examples using PLT4M’s diverse range of curriculum and high school lesson plans.

During instructional units, teachers can use formative assessments to track progress and get a sense of how students are experiencing the delivery of curriculum. Formative assessments help guide future instruction with student input. Plickers is a technology tool that is gaining popularity with elementary PE teachers. Plickers assign a QR card to each student, often laminated and magnetized. Teachers pose questions to students, and they rotate their card to give their answer. Teachers then use their phone to quickly scan responses and see student answers immediately.

It is also critical to understand the lens through which student experience their lives and educational experience. A key tenant of culturally responsive practices is student-centered learning.

Needs-Supportive Student Centered Learning Examples

When teachers build relationships with students and create safe learning environments, students are more willing to try new strategies (Cothran, 2001). Teachers should create motivating environments that accommodate diverse learning abilities.

Autonomy, relatedness, and competence are the three psychological needs that make a person more self-determined (Ryan & Deci, 2000). When students have the autonomy to create individual goals, are provided the knowledge and skills to progress towards those goals, and do so in a social-supportive environment, they are likely to be motivated to be physically active. A needs-supportive environment focuses on the needs of the student, rather than the need of the teachers (Washburn et al., 2016).

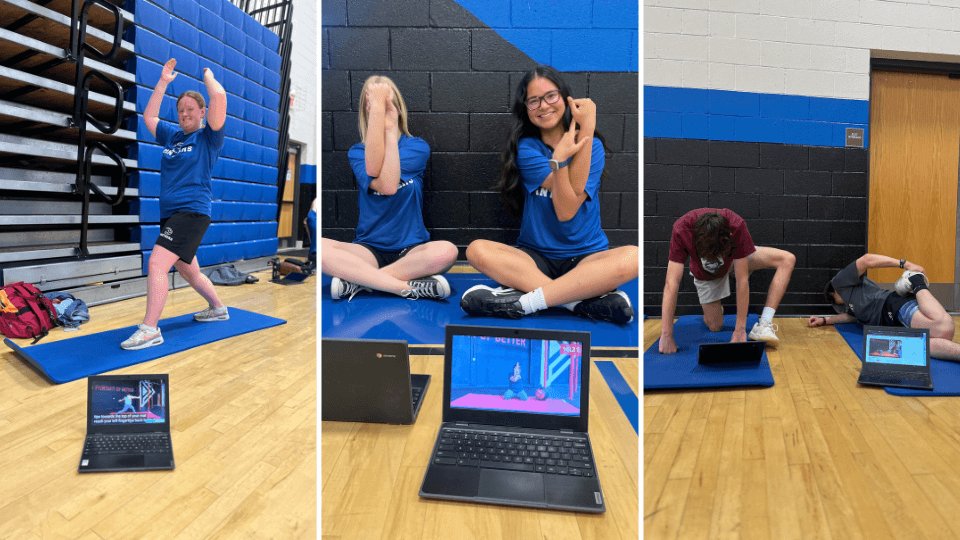

Through an inclusion teaching style, teachers can provide choices of exercises for students and health-related fitness activities that are specific to their personal goals. Cooperative learning activities that include peer support can stimulate relatedness. Differentiated instruction can promote competence with students of all ability levels feeling they can be successful.

Differentiated Instruction Framework

Differentiated instruction strategies are student centered learning examples that accommodate a diverse range of student abilities (Colquitt et al., 2017). The framework includes assessing students’ readiness, providing process-support, and measuring the product of learning in a manner that is accessible to students.

Students’ readiness state can be considered pre-assessments or baseline tests that gauge where a student ability level is currently at. The Brockport Fitness Assessments provide 27 health-related fitness assessments for students of varying physical abilities (Winnick & Short, 2014). For example, a modified pull up test or isometric push-up test can be used if a student is not ready to perform a complete pushup when assessing muscular endurance. Teachers can provide process-support through accommodation and modifications of exercises to promote competence.

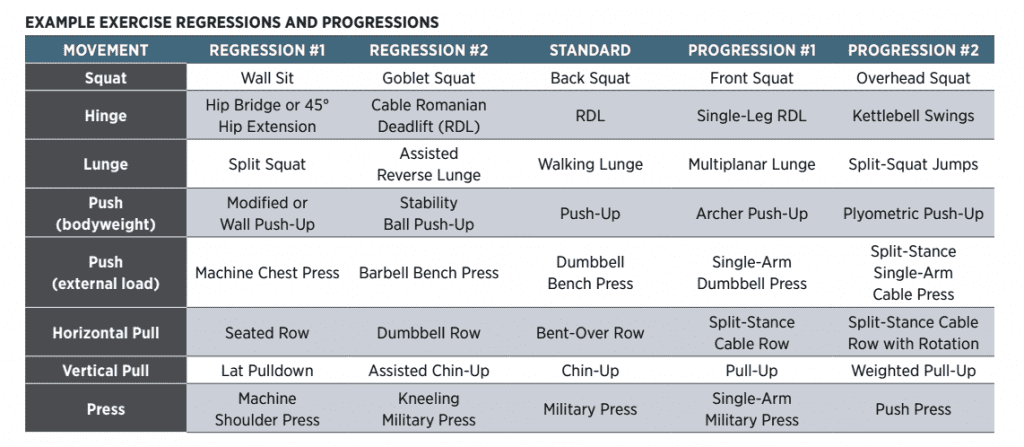

For example, exercise progressions or regressions can be applied to accommodate varying ability levels. See “Example Progressions and Regressions” from the NSCA that can be applied (Clayton et al., 2015). Summative assessment for measuring the product of learning should include a mix of modified assessments, project based learning, fitness portfolios, presentations, and cognitive assessments.

Bonus Content: PLT4M Instructional Video showcasing modified push up.

Key Takeaways on Student Centered Learning Examples

- Align curricular models that help student meet the standards through relevant learning experiences (Treadwell, 2013).

- Use student input when creating curriculum and delivering instructional strategies.

- Provide learning experiences that are needs supportive (i.e. autonomy, competence, and relatedness) (Washburn et al., 2016).

- Apply differentiated instruction to accommodate diverse ability levels.

- Allow students to display summative learning in multiple ways.

References:

Colquitt, G., Pritchard, T., Johnson, C. McCollum, S. (2017) Differentiating instruction in physical education: Personalization of learning. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 88:7, 44-50, DOI: 10.1080/07303084.2017.1340205

Cothran, D. J. (2001). Curricular change in physical education: Success stories from the front line. Sport, Education and Society, 6(1), 67-79. doi:10.1080/713696038

Clayton, M., Drake, J., Larkin, S., Linkul, R., Martino, M., Nutting, M., & Tumminello, N. (2015). Foundations of Fitness Programming. National Strength and Conditioning Association.

Curtner-Smith, M.D. (1999). The more things change the more they stay the same: Factors influencing teachers’ interpretations and delivery of national curriculum physical education. Sport Education and Society, 4, 75–97.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54-67.

Ferry, M., McCaughtry, N. (2015). “Whatever is comfortable:” secondary physical educators’ curricular decision making: Issues of knowledge and gendered performativity. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34, 297-315.

Ferry, M., McCaughtry, N. (2013). Secondary physical educators and sport content: a love affair. Journal of Teaching Physical Education, 32, 375-393.

Ison, S. E., Jakaitis, T., Richards, K. A. R., & Pennington, S. (2021). redesigning high school physical education curricula to meet students’ needs. Strategies, 34(2), 50–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2021.1867456

Lund, J., & Tannehill, D. (2015). Standards-Based Physical Education Curriculum Development (3rd ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Simonton, K. L., Washburn, N. S., Prior, L., Shiver, V. N., Fullerton, S., & Gaudreault, K. L. (2022). A retrospective study on students’ perceived experiences in physical education: Exploring beliefs, emotions, and physical activity outcomes. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education.

Washburn, N., Richards, K. A. R., & Sinelnikov, O. (2016). Advocating for more student-centered physical education: The case for need-supportive instruction. Strategies, 29(6), 37–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/08924562.2016.1234162

Winnick, J. P., & Short, F. X. (2014). Brockport Physical Fitness Test Manual. Human Kinetics.