The key to any successful monitoring strategy in sports is having buy-in from the athletes. Without athlete buy-in, it will likely be difficult to get reliable and valid data.

Of course, what an athlete being ‘bought-in’ looks like may vary greatly, from an individual who is simply happy to trust in the process and comply with whatever they are asked to do all the way through to an individual who is fully engaged and involved with the process that acts as a sponge to whatever you can share with them. But how do you gain that buy-in from your athletes?

Strength and conditioning staff at one of Firstbeat’s customers emphasized that it’s all about building a culture within the building and getting your athletes to trust what you are asking them to do.

The culture has just been developed over the years but even more so in the last season or two, where we have involved senior players in the management of the group, to ensure that the players hold standards high and are accountable if they don’t wear the units”

The question of how to do that is a difficult one to answer and there’s definitely no one-size fits all solution, so this blog isn’t going to pretend there is. Instead, I’ll take a look at some theory that I think is relevant and attempt to provide a framework for motivating your athletes to engage in the monitoring process. In addition, I’ll provide some thoughts from practitioners working on the front-line in order to help your form your own ideas that fit the context of your specific group.

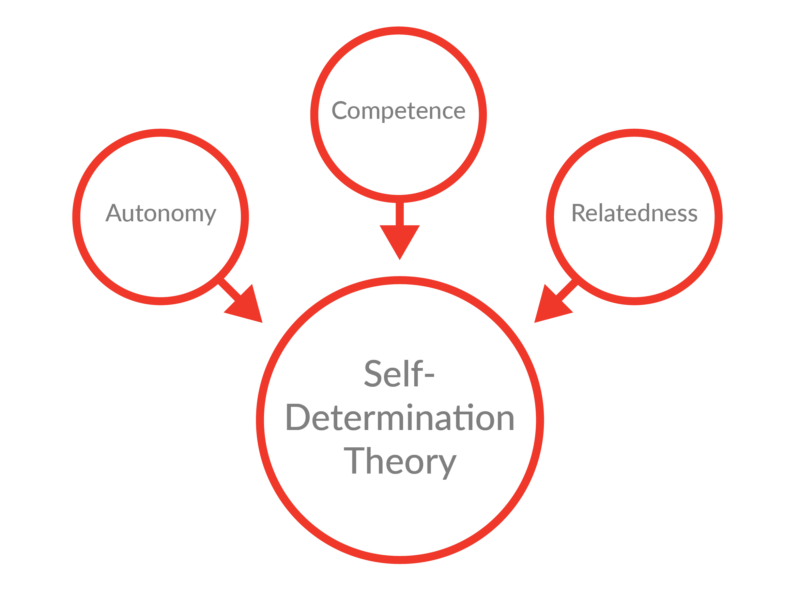

Self-Determination Theory

When putting together the background research for this article, one psychological theory that immediately came to mind was Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, 2000) which I will use as a framework for harnessing athlete buy-in. In brief, it seeks to explain what drives the intrinsic motivation behind the choices that people make and there are three components to SDT; from these I think you’ll begin to see where I’m coming from and why I chose to use this for the basis of this piece.

The theory proposes that an individual must feel autonomy, competence, and relatedness in order to be intrinsically motivated to engage in a behavior, with greater feelings in these areas leading to greater levels of motivation. By devising strategies to enhance these three areas you will have athletes who are motivated and buy-in to your monitoring strategy. We could also look at introducing external motivation factors, such as rewards to compliance or perhaps the more commonly seen punishment for non-compliance, but external motivation is rarely as robust when it comes to forming long-term habits.

Performance monitoring in an athletic context is a long-term project, so we want our athletes to be in it for the long-haul and not reliant on external carrot-or-stick strategies for maintaining that compliance.

Autonomy

Autonomy is perhaps the most challenging part of the model when it comes to monitoring your athletes. SDT posits that an individual wants to be in control of what they do, and giving someone this control will help to increase intrinsic motivation (Zuckerman, et al., 1978). But how do we offer autonomy with something that we essentially want to be compulsory in order to get a complete picture of the athletes’ training status? After all, you’ve just invested in your new monitoring system, so you want to ensure your athletes are using it to get a return on that investment.

Another Head of Performance mentioned the importance of giving players choice where they can, so while it is expected that they will wear their Firstbeat Sports Sensors in pitch-based training, they are given the option in other circumstances. The Manual Exercise Input feature in Firstbeat Sports helps support this approach, allowing you to input training load for ‘missed’ measurements and maintain more accurate longitudinal training load data. Therefore, you should consider ways in which you can create the illusion of autonomy if you’re not able/willing to provide complete autonomy to your athletes.

Examples could include mandating the wearing of a Sports Sensor in pitch-based sessions but making it optional for the gym, letting athletes choose whether to wear it in competitive fixtures, or with the Quick Recovery Test giving the athlete the choice to record the test at home using our Athlete app or at the training ground. The QRT example is worth keeping in mind as the decision doesn’t need to be an all-or-nothing option, it can simply be a choice of where/how the measurement is taken that creates that feeling of autonomy.

Competence

The competence part of SDT proposes that an individual needs to feel mastery of a task and learn new skills in order to facilitate intrinsic motivation. This is an interesting one within the context we are talking about here, as the athlete is not solely responsible for the management of their training load. Indeed, they may ultimately have little responsibility outside of the wearing of the device(s) as sports science or coaching staff will likely be the ones doing the monitoring.

However, a greater feeling of understanding the data should aid in intrinsically motivating them to do what is being asked which isn’t really surprising; if you’re being asked to do something in any part of your life you’ll generally want to know why, athlete monitoring is no different. Research has indeed shown that greater feelings of competence aid in persistence and motivation to engage in an activity (Guillet, et al., 2002; Ntoumanis, 2005)

What can we as staff do to help nurture the feeling of competence? Holding educational sessions may be one option, explaining what you are doing and why you are doing it, but this is only one piece of the puzzle. Using understandable terms will also help when discussing data with your athletes or providing session feedback. For example, you could swap out aerobic for endurance, anaerobic for high-intensity or high-energy. One of the key areas, however, will be using opportunities to speak one-on-one with your athletes, this will not only allow a more personal level of interaction but also give some insights into what is important to that individual.

This was one of the other points raised when speaking with some of our customers; you as a coach need to find opportunities to capture the athlete’s interest. Once such opportunity is during rehab or one-to-one conditioning as you can frame and explain things in a context that is entirely specific to the athlete at that time, they can feel what you are explaining and experience the data first-hand. You can then listen to the athlete and their questions much more clearly in that one-to-one environment and use that to educate, as well as have more time for conversations with them.

Relatedness

The final element of the model is relatedness or connection. This states that humans need to have a feeling of belonging and connection to others to harness intrinsic motivation (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). An important consideration here is getting senior members of your group on board and having the athletes hold each other to account. Therefore, it is worth concentrating your early efforts on those who fall into that category, but also those who are more likely to engage and be motivated. Once you begin to get these ‘early adopters’ on board, the middle ground of the group will soon follow. There may still be a resistant minority but they too will likely see their interest and curiosity grow as it becomes an accepted part of your training routine.

Aside from talking to and educating your athletes, covered when discussing the competency part of the model, there are other practical things you can do to build a sense of relatedness. Share group reports with information that is most pertinent to the athletes, but don’t exclude those who are not engaging in the monitoring process. Instead, leave a space where their data would otherwise be. This shows them that they can easily be more involved with the rest of the group, and again allow the opportunity to see the data, how it is being used, and how others are benefiting from it. Obviously, this overlaps somewhat with the other parts of the model we’ve already discussed and emphasizes that they are part of a larger model rather than being discreet entities, so try to consider all aspects when planning your interventions.

Building Trust

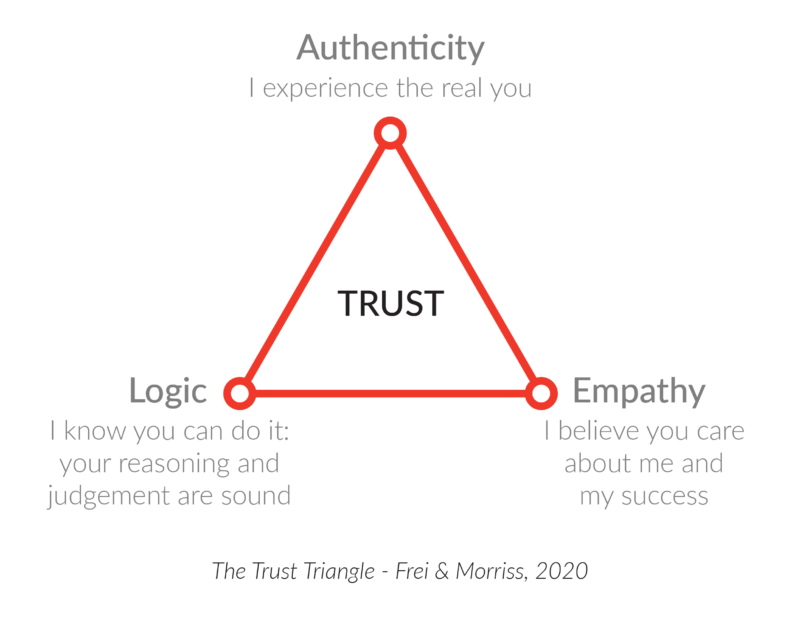

A huge part of any process within coaching and getting the most from your athletes, whether you’re a head coach, sports scientist, nutritionist, or any other of the myriad of roles that exist in elite sports these days, is building trust with your athletes. Without them trusting you and the process you are implementing, it is unlikely to be successful. Having the trust of your athletes is vital; even if your athletes aren’t super interested in the monitoring process, if they trust you they’ll be happy to comply with what you are asking of them and do what they need to do for the process to be successful.

I’m not going to delve too deeply into this, but Frei and Morriss (2020) present a model for building trust and the elements you must present for someone to trust you. Each of the components, Authenticity, Logic, and Empathy can easily be applied to the context of working with your athlete(s). For example, do they believe your reasons for monitoring are sound, are they truly for the benefit of the athlete and their performance, and is this true to your actual beliefs? I’m not saying following the Trust Triangle is a quick fix, clearly it will take time to build each component, but being conscious of your behaviors and how they relate to the trust process will put you in a good position going forward.

Summary

Building intrinsic motivation and trust with your athletes are key components of any monitoring program. This is one of those tricky areas where every context will be different, what works for one group won’t for another, sadly it’s not as ‘easy’ as fundamental physiology, EPOC is EPOC wherever it occurs! You’ll have your own specific constraints and challenges to deal with, and even each individual athlete within a particular context will likely require some adjustments specific to them so be mindful of this if you work with larger groups.

While this piece hasn’t tried to give you definitive answers on how to do that, using something like SDT or some other intrinsic motivation theories as a framework will put you at a solid starting point. Hopefully, this article has provided some food for thought and will aid in generating ideas and strategies to facilitate the motivation and trust we all want to build with our athletes.

Do you have any questions, comments or wish to share some of your own success stories? We’d love to hear from you!

If you found this article interesting, be sure to check out our free guides on athlete well-being and athlete training load.

References

Baumeister, R., & Leary, M.R. (1995). The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Frei, F.X., & Morriss, A. (2020). Managing People: Begin with Trust. Harvard Business Review, viewed 12 October 2021, <https://hbr.org/2020/05/begin-with-trust>

Guillet, E., Sarrazin, P., Carpenter, P. J., Rouillard, D., & Cury, F. (2002). Predicting Persistence or Withdrawal in Female Handballers with Social Exchange Theory. International Journal of Psychology, 37(2), 92-104.

Ntoumanis, N. (2005). A Prospective Study of Participation in Optional School Physical Education Using a Self-Determination Theory Framework. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 444-453.

Ryan, R.M., Deci, E.L. (2000). Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78.

Zuckerman, M., Porac, J., Lathin, D., Deci, E.L. (1978). On the Importance of Self-Determination for Intrinsically-Motivated Behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 4(3), 443-446.

You might also be interested in

How to Use Firstbeat Sports in Practice – A Quick Guide for Coaches

Coaching a sports team requires careful management of training, player performance, and recovery. Making informed decisions is crucial to maximize your team’s potential and achieving success on the field. One…

Heart Rate Recovery Feature from Firstbeat Sports Provides More Insights for Coaches

The new Heart Rate Recovery (HRR) feature from Firstbeat Sports provides an additional tool for coaches to assess the status of their athletes, giving further insights into conditioning and recovery…