Written by Andy Driska, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor and Coordinator of Sport Coaching and Leadership Online Programs

Here’s why modifying equipment, changing playing dimensions, changing rules, and gamifying practices – all examples of task constraints – are better strategies for teaching and refining athletic skill

Perhaps the most important goal for coaches is developing the movement skills of their athletes. Technical skills are the movements used by individual players to achieve important game outcomes, like shooting a basketball jump shot, or putting a shot on goal in soccer or lacrosse. Tactical skills are the movements used by a team to achieve an important game outcome, like a soccer team pressing the ball towards the opponent’s goal, or a water polo team running a power-play defense. Tactical skills also apply to individual performances, like a wrestler trying to execute a performance strategy, or a runner or swimmer following a race plan.

So, what’s the best way to teach these skills? Consider some examples first.

Let’s say you’re a lacrosse coach teaching a player to shoot the ball on goal. You want to see the player extend their arms more in the shooting motion, because that will give the ball more velocity. How do you get the player to extend their arms more?

Or let’s say you’re a basketball coach teaching a player to make a jump shot. You want the player to bend their knees more, and you want to see backspin on the ball. How do you get the player to bend their knees and flick their wrist to get backspin?

The answer is simple, right? Just tell them to extend their arms, or bend their knees, or flick their wrist.

If you’ve spent enough time coaching, you’ve probably realized that telling an athlete how to perform a skill has mixed results. Some players take the instruction and turn it into an ideal motion right away. Some players might use the ideal motion in structured practice situations, but in game situations the skill breaks down or returns to its previous state. And some players struggle to use your instruction at all. And that’s just on the player’s side, because often times what coaches think is good instruction is actually an unorganized 2-minute ramble about how the body should look while performing the skill. Who knows what a player will take from that message?

The lack of positive results following instruction can frustrate a coach, but the problem does not lie in the player or their ability to listen and comprehend.

The problem lies with instruction. Telling players how to move is not the most effective means of teaching or refining a movement skill. Giving instructions often puts you into the trap of assuming there is one correct way of performing a skill. In reality, there are a range of acceptable ways to perform a skill. That range will depend on the player and the situation. Take for example the basketball jump shot – how many times in a game will the shot be performed in exactly the same way? Game situations dictate how the shot will be performed. The distance from the hoop and the type of defense being applied will influence the pattern of the shot. The physical characteristics of the player matter as well. A shorter player might need to bend their knees and jump in order to clear a defender, whereas this might not be necessary for a taller player.

3 Problems with Giving Instructions

- Giving instructions often puts you into the trap of assuming there is one correct way of performing a skill. In reality, there are a range of acceptable ways to perform a skill. That range will depend on the player and the situation. Take for example the basketball jump shot – how many times in a game will the shot be performed in exactly the same way? Game situations dictate how the shot will be performed. The distance from the hoop and the type of defense being applied will influence the pattern of the shot. The physical characteristics of the player matter as well. A shorter player might need to bend their knees and jump in order to clear a defender, whereas this might not be necessary for a taller player.

- Instructions don’t present a strong enough sensory stimulus to develop an ideal movement pattern. Human movement is largely controlled through perceptual-motor systems that operate somewhat independently from cognitive systems that handle instruction. Without getting into too many details (we’ll do that later), consider how infants and toddlers learn to move. Typically, adults place them in situations that encourage them to move, such as supported standing along a coffee table, or by holding an interesting toy in front of an infant getting ready to crawl. We don’t provide instructions on how the toddler should move their arms and legs. Instead, we place an object in front of them that creates a movement goal, and while we support them we let them figure it out. This logic doesn’t change much as we age and develop a range of movement skills. The challenge for a coach is to find away to apply this logic in an age-appropriate manner, by creating a clear movement goal but allowing the player wide latitude in finding a solution.

- Instruction can often put you in the trap of repetition. The assumption is that by performing the skill over and over in the same way, we are creating an imprint of how the skill should be performed. Many coaches say they are trying to build “muscle memory,” which is the idea that an oft-repeated skill will be more likely to hold up under fatigue, stress, and game pressure. The problem with repetition is that variation is a good thing. As I noted previously, any skill will be performed under a range of conditions in a game. No two jump shots will look alike. Yet, if we practice repetitive jump shots under controlled conditions with little interference or variation, the player will be less prepared to take varied shots in the uncontrolled conditions of a game.

So, the challenge for coaches is to use a method of skill instruction that:

- does not prescribe a “correct way” of performing the skill

- does not tell a player how to move, but instead creates a clear movement goal and allows the player to figure out a solution

- does not become repetitious, but instead allows for more variation in how the skill is performed

If this has attacked your entire coaching playbook, I apologize. I wouldn’t do this unless I was planning to discuss a better form of skill instruction called the constraints-led approach to coaching skill.

Using a Constraints-Led Approach

The major take-home on the constraints-led approach is that rather than using excessive instruction on how a player should move, the coach constrains a player’s movement possibilities through the use or modification of equipment, changes to the playing dimensions or surfaces, changes to rules, or the use of games. These coaching strategies are called task constraints. Let’s explore some sport-specific uses of task constraints.

Modifying Equipment

Using specialized equipment or modifying standard equipment is probably the easiest and most common use of a task constraint. If we want a basketball player to use a high arc on a jump shot, then we need to constrain the pathway of the ball. The simplest way to do that is with a barrier – any shot with a low arc will hit the barrier, giving strong sensory feedback to athlete about the path of the shot. The barrier constrains movement possibilities in that only the shots with high arc will have a chance at getting over the barrier and going through the hoop.

A barrier can be used with our lacrosse player as well. If she doesn’t extend her arms, she won’t be able to get the shot around the barrier. However, extending her arms might cause her to lose control of the ball. She might need to spend some time practicing to find an ideal solution to the problem of getting the shot over the barrier but keeping the shot aimed at the target of the goal. This is where modifying the standard equipment might be useful if the player struggles. Instead of using a women’s lacrosse stick, which has a shallow pocket making the ball more likely to fall out, use a men’s lacrosse stick which has a deeper pocket that makes ball control easier. Let the player develop shooting skill with the barrier in place, then progress back to using a women’s stick.

Throughout both of these examples, the coach has limited their instruction to explaining the goal of the task (shoot the ball on net, and obviously try to avoid the barrier). The player has done most of the work, experimenting and playing with different solutions to getting the ball around the barrier and into the net. If you videotaped 20 players successfully shooting over a barrier and superimposed their video, I’m willing to bet that you would see 20 different solutions to the same problem, proving our point that there is not one correct way to perform a skill.

Changing Playing Dimensions

Changing the amount of space that players have to perform technical and tactical skills can have a profound effect on the way the skill is performed or the play unfolds. For years, coaches and researchers have noted how the sport of futsal can develop better ball handling skills in soccer players. A primary reason is the lack of space. A futsal court is 40m x 20m (800 square-meters), while a soccer field is 110m x 75m (8,250 square-meters). Futsal crams six players into a space only one-tenth the square footage of a soccer field, and so the game is fundamentally changed by the constraints on space and movement potential. Frequent passes are much more likely to be intercepted, and players are pushed towards dribbling and keeping the ball closer to the body. The technical skills of dribbling and passing are constrained by these new dimensions, but tactical aspects of the game are constrained as well, as passing and scoring options unfold and disappear quickly. Decision-making happens much faster, or the ball is lost.

I think many coaches do this intuitively, without realizing that this approach is validated by science. One of my early lessons in coaching water polo was preparing to play at a very old pool, which was only 30 feet wide as opposed to the typical 48-foot width of our home pool. A mentor coach suggested that for our lead-up practices to this game, we should just put lane-lines in our home-pool to narrow the court. It took an entire day of practicing before player strategy evolved to fit the new playing dimensions. I could have told them repeatedly to make shorter, crisper passes, but there is no substitute for playing and practicing under the constrained playing dimensions. Those perceptual-motor processes must be developed through real experiences

Another great example is Quick Start Tennis (10 & Under Tennis), which my colleague Jennifer Nalepa has written about extensively. The playing dimensions are scaled to the size of the players, with one-quarter the space of an adult court, and a lower net-height. These changes constrain the playing space, which push the game towards a natural, back-and-forth rally. Quick Start Tennis also uses modified playing equipment – smaller rackets and balls that don’t bounce as fast as the adult ball. Along with the changed dimensions, these changes make the game more natural to play without extensive instruction and direction from a coach.

Changing Rules

Rules of the game impose an interesting constraint. If you have ever tried to teach new players the rules of a game, you know that it is difficult to turn cognitive instruction into action. Rules are best kept simple. Explaining the “spirit” or purpose of a game might be effective. Soccer has a very simple purpose – put the ball into the other team’s net without using your hands. Perhaps that’s why it’s the most popular sport in the world? Basketball can be summed up simply as well – put the ball through the hoop, but if you want to move you need to bounce the ball under your hand. These rules, kept simple, give players some basic direction and allow pick-up game play without extensive instruction and regulation.

Rule changes constrain the development of new skills and techniques. For example, in swimming, when the 15-meter underwater swimming distance was established, it changed the importance of underwater kicking. Underwater kicking – usually dolphin kicking – became the “5th stroke” and received much more attention in training regimens. Today’s high-school swimmers kick underwater better than their adult counterparts from 30 years ago.

Rule changes during a practice drill can constrain tactical skill development and are arguably more effective than a coach trying to direct traffic. Taking 10-seconds off a shot clock can help push a fast-break offense. Sudden 20-minute player exclusions, creating an advantage for one team, can show players new looks and create new potentials for movement and skill development.

However, some rule changes could diverge too far from the purpose of the game, and develop habits that might be counterproductive. For instance, a practice scrimmaging rule that players must complete 5 passes before taking a shot might not be productive. I understand the intent of making that rule – you want your players to pass more often and understand about how passing can open-up better looks for a good shot on net. But what if the best shot opportunity opens after pass #3? Your player will overlook their natural perception of a good shot opportunity in order to conform to the rule. That won’t help their ability to perceive good shot opportunities during a game situation. This rule goes against one of the principles of constraints-led approaches to coaching, in that the rule is telling players how to play the game, rather than letting them use their perceptual-motor capabilities to figure it out under an appropriate set of constraints.

A good question to ask yourself when imposing a practice rule – does the practice rule bend too far from the goal of the “master” game? If it is too different, the odds are that it will be teaching your players to prepare for a different type of game.

Gamifying Practice

If you quickly think of the practice activities that your athletes are most excited to do – where they know the rules, where you don’t have explain too much, where they are active and motivated and give full effort – chances are that this activity is very much like a game. The idea is not new to many coaches and teachers, and the Teaching Games for Understanding movement has done a great job of developing games that make skill learning and development more interesting and effective, for both athletes and coaches.

A few important things to consider about games:

- Does the practice game contribute to some set of skills or tactics that are important for the “master” game?

- Is there a very clear object of the game, or is the game plagued by rules?

- Does the game have an ideal amount of challenge? If it’s too easy or too difficult, can you scale it up or down so that the level of challenge meets the skill of the players?

- Is it likely that players would engage in this game on their own?

One of my favorite games to play as a high school soccer player was a game we called World Cup. Players paired up and chose a country to represent. We had about 15 countries (30 players) all packed inside the penalty area – everyone on offense, and no goalkeeper. The object of the game was to be the last person to touch the ball before it went into the goal, which would move your country along to the next round. Ideally, you might pass to your teammate and he would head the ball into the net, but it rarely happened that way. It was much more chaotic, and that was the set of skills and tactics the game contributed to – the chaos that ensues on a loose ball in front of the net.

Later in my coaching career, I adapted the game for water polo. A fair amount of goals in high school water polo are scored on messy, loose-ball situations directly in front of the net. There was no better drill or instruction for teaching players how to handle this chaotic situation. It was also the most effective way to teach new players the 2-meter (off-sides) rule. A chaotic, challenging, and fun game created the best conditions for athletes to learn a complicated rule.

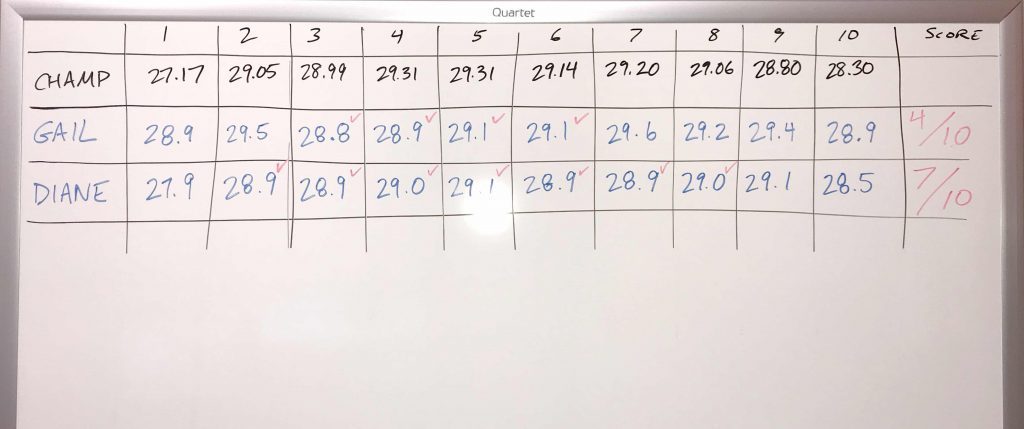

Games are not limited to teaching the tactical aspects of invasion sports. They can be used to bring excitement, interest, and focus to difficult training for endurance sports like swimming and running. One of my favorite go-to training sets in swimming was a game called Beat the Champ, first explained to me by Bob Steele, and also explained well in his book Games, Gimmicks, and Challenges. Steele was advocating for constraints-led approaches maybe without knowing it was a thing (with a name and an evidence-base supporting it). Whether he knew about the constraints-led approach or not, he stuck with these approaches because they worked.

Beat the Champ was my favorite game because it had such a simple design and we could apply it to almost any group of swimmers. We’d find the 50-yard splits for the winning 500-yard freestyle swimmer at nationals the previous year. We’d write the splits on a whiteboard. Then, the swimmers would swim 10 x 50-yard repeats on a 1-minute interval, and try to beat each of the champ’s 50-yard splits. Once a swimmer could beat all ten splits, the next time we’d give them less rest, using a 55-second interval. The goals were clear, the challenge was fun and scale-able, and it served as a yard-stick of the swimmer’s progress throughout a long season. It also got us away from boring, repetitious workouts – “busywork” – and put our focus on work that would help us perform better at our final meet.

Concluding Thoughts

Using the constraints-led approach is a mindset shift for a coach. You must shift from the instructor-in-chief to a caretaker. You are not providing critique, but changing up equipment, rules, and boundaries to get the ideal skill results. You’re being creative and coming up with new games for practices. Or you’re doing what most coaches do… just stealing great ideas from other coaches. That’s not the command-style orchestration you might be accustomed to. But I challenge you to think about how well that command-style approach really works.

As with any new method of coaching, it’s critical to devote more time to planning your practices, being aware of how you react when you see a player struggling with a skill, and reflecting early and often on what’s working and what needs adjustment.

In my next post, I will dig deeper into the science and theory behind constraints. I’ll discuss individual and environmental constraints, which also shape the way skill is learned, developed, and refined. Stay tuned.

Helpful Resources

Dynamics of Skill Acquisition – A Constraints-Led Approach. (2008). Keith Davids, Chris Button, and Simon Bennett. Human Kinetics Publishers.

This is a college-level textbook that provides scientific theory and practical examples regarding the constraints-led approach.

The Constraints-Led Approach – Principles for Sports Coaching and Practice Design. (2019). Ian Renshaw, Keith Davids, Daniel Newcombe, and Will Roberts. Taylor and Francis.

This is a new college-level textbook that I have not read yet, but have heard great reviews from a few of my students.

Teaching Games for Understanding website

This website provides examples along with research explaining its effectiveness.

Interview with Keith Davids, Sheffield Hallam University, Constraints-Led Approach to Skill Acquisition. (2016). Keith Davids and Rob Gray. Perception-Action Podcast.

Rob Gray’s Perception-Action podcast is a great resource for all-things skill acquisition. He has interviewed many leading scientists and coaches on topics like skill acquisition, talent development, and sport psychology