Introduction

For me, Social Justice is the ‘20s era equivalent of SEND. It is a term we have all come across and know we should understand a little better but are a too embarrassed to ask about in case we offend anyone. This book by Shrehan Lynch, Jennifer Walton-Fisette and Carla Luguetti was published by Routledge in 2022 and provides a reader friendly exploration of issues and contemporary debates in social justice and equity within Physical Education (PE) and Youth Sport (YS). Reading it will challenge and support you to be more critical of the status-quo and enable you to advocate and enact more socially just approaches to inclusion and inclusive practice.

The authors all have important lived experiences to share and reflect on as they carefully articulate the importance of increased awareness and action. I challenge anyone to read this book and not feel motivated to do more.

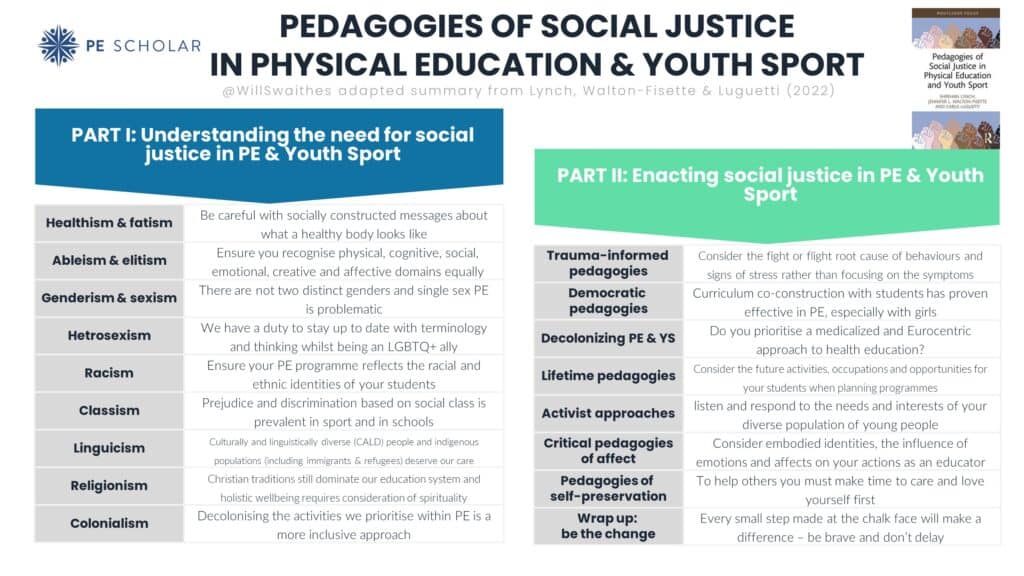

The book is divided into two parts. Part I will help you understand nine key areas of social injustice with a summary of the research and examples of what that looks like in practice to aid exploration. Part II discusses and outlines socially just pedagogies and approaches to curriculum, content, and delivery with practical examples to help you consider implementation.

Part I: Understanding the need for social justice in Physical Education and Youth Sport

Valuable terminology relating to social justice provides an excellent starting point for the book to include a recognition that definitions and concepts change over time as a response to socio-cultural and political pressures. The following diagram summarises some of the key terms defined:

1. Healthism and fatism

Socially constructed messages about what a ‘healthy’ body should look like often reinforce a binary view of slim females and muscular males that triggers and is fuelled by fad diets and calorific expenditure. Social media and many role models have had a negative part to play in this ‘fatist’ culture that fails to notice the holistic contributions of mental, emotional and social health. Read this thought provoking blog by Laura Davies who also contributed a case study in this book to consider this more. Reflecting back, part of the GCSE PE syllabus for as long as I can remember has included a benefit of physical activity as ‘looking good – feeling good’ and consequently the harm that can be done by reinforcing this messaging is clear to see for some individuals. Keen readers should also consider this book review on ‘Physical Educatuin Pedagogies for Health’ by Jo Harris and Lorraine Cale and the work of Dr Vicky Goodyear who is leading the way when it comes to the influence of social media and digital technologies on young peoples perceptions of health.

You are encouraged to think carefully about your everyday language but also the way in which health and fitness is covered in your programme. Suggested approaches that are more critical and considered include stimulating ‘conversations on nutrition, fad diets, diet pills, or any kind of “quick fixes” that will cause a person to look as expected according to the socially constructed gendered ideal’ (p10). We are reminded to recognise the impact of social identity, body types, access to exercise and nutritious food, not to mention mental health, when it comes to perceptions of health. Lynch et al. remind us that solutions such as exercise and eating well are not as simple as they may sound in a complex socio-cultural world.

2. Ableism and elitism

Ableism is an ideology that oppresses individuals with a disability. Simply challenging your perception of what is ‘normal’ would be a recommendation I have for many when considering a range of topics in this book. Let’s be honest here, particularly within secondary schools with how classes are grouped, there has been a long held pattern of recognising, rewarding and privileging those who are more physically able – perhaps more accurately those who have benefitted from early maturation or more early exposure to sport. Lynch et al. remind us that not all young people have the same aspirations or narrow view of what success looks like, so it is essential we ‘encourage collaboration, creativity, discussion, and enjoyment’ (p14). Whilst many of us now include opportunities to experience and appreciate disability sports within our PE curriculum, we are reminded to avoid tokenism and critically consider the best ways to do this with different cohorts. How do you avoid the damaging practice of setting by ability or prioritising sports such as football, rugby and netball over seated volleyball or boccia? How well do you recognise ‘social, emotional, creative, and cognitive’ domains of learning as equal to physical?

3. Genderism and sexism

‘Genderism, or gender binarism, is the belief that there are two distinct genders, male and female, that are directly linked to the sex assigned at birth’ (p18). This way of thinking is incredibly harmful, as is the historic sexism that has run rife through sport to suggest one sex or gender is superior to another. As practitioners, we must challenge stereotypes around gender roles. Do you offer single or mixed-sex PE? What informs these decisions in your school and with different cohorts? How do you overcome the challenges of changing rooms to ensure all students feel safe and comfortable?

One small step you could make to ensure young people feel in a safe place to be themselves is to share your pronoun with students or wear a rainbow lanyard. Be an active ally and leader who supports students to understand and appropriately use terms such as gender identity, non-binary, intersex and trans.

4. Heterosexism

The prejudiced belief that heterosexuals or “straight” people are normal or ‘superior’ has led to ‘homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, and overall LGBTQ+ phobia’ (p23). Bullying, exclusion and alienation are all commonplace for individuals who identify as LGBTQ+ according to research (p24).

We all have a duty to stay up to date and better understand key terminology and perceptions to support students to use the language correctly and obviously challenge prejudice robustly. It is also important to recognise the added challenges when you combine sexual identity with religion, something I have become aware of with a student I worked with. If you haven’t heard it already, I highly recommend the Sam Smith episode on Michelle Visage’s rule breakers podcast available on BBC sounds.

5. Racism

‘Anti-racism is a form of action against racial hatred, bias, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racialised groups’ (p28). Harrison and Clark (2016) argue that ‘research on race and other social identities is limited and marginsalised because, most often, the research is conducted by marginalised people. Again, there is clear room for improvement here and whilst movements such as Black Lives Matter are helping, more can be done. What anti-racist behaviours do you employ in your school? Even simple measures to learn the correct pronunciation of students of colour’s names and avoid the use of ‘a nickname or Western name instead’ (p29) is a good place to start for many. How well do the activities you programme as part of your curriculum reflect the racial and ethnic identities of your students? Links are made to trauma that some young people face within our ‘movement spaces’ and sport (p31). Watch this space for more we will be doing around trauma informed PE soon!

6. Classism

Prejudice and discrimination based on social class still prevail in PE, sport and society. Lynch et al. found a strong association between income inequality and health conditions linked with morbidity, mortality, and obesity’ (p33) and this is also depicted each year in Sport England’s active lives reports. As a consequence, this is absolutely something we should concern ourselves with but in doing so be very careful with how we use terms and categories like disadvantaged, deprived, vulnerable, pupil premium and free school meals. Compare activities like boxing and wrestling with sailing and golf to see a long history of classism at work in sport. Social mobility is hot on the agenda for many education policies so what are you doing to champion this in PE and youth sport spaces? Oppression and privilege are significant concerns when we look at the skewed data amongst youth and senior sports representation from private versus state school backgrounds respectively. Again, the authors remind of the interactions of class with gender, race/ethnicity and sexuality in particular.

7. Linguism

Discrimination against those for whom English is an Additional Language (EAL) here in the UK but also ‘directed at culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) people and indigenous people (e.g. immigrants and refugees)’ (p40) is something I remember the media picking up on when Alex Scott was presenting on the BBC at the Tokyo Olympics. Racist trolls targeted her accent and as a consequence I hope many of us will be far more considered before questioning young people on “speaking properly”! Whilst PE is a movement (practical) space and hence transcends language to some extent, we must also remember that it is plagued with technical terminology that many of us take for granted. Again I am reminded of the reading age required to access the GCSE PE examinations and how many of our young people fall below this threshold, and not just those with EAL. If you haven’t seen the Netflix documentary ‘The Swimmers’ about two Syrian asylum seekers yet then I highly recommend it and discussing it with your students. Plenty to unpick around belonging, challenges of adversity and hope.

One nice example of how you could teach and explore the topic of linguicism is to ‘ask young people to create a timeline of their experiences in PE and/ or YS… represent[ing] particular critical incidents (educators, competitions, activities) that influenced their motivation’ to participate (p41). I have tried this with my trainee teachers and it was fascinating to here the similarities and differences between individuals before unpicking what that did to their attitudes, motivations and feelings towards physical activity.

8. Religionism

Discrimination or prejudice based on religious beliefs can be seen in many school traditions that are influenced by Christianity, a privileged and dominant religion (p44). This chapter flags the importance of spirituality when it comes to holistic wellbeing and challenges us to think about the impact of practices like wearing a hijab or fasting on inclusion in PE. Lynch et al. highlight how many of the practices within school to include when we have holidays (Christmas and Easter) privilege Christianity. An interesting suggestion is made that schools could rotate their holidays year on year to represent the different religious followings of their community. For example, I work with trainee teachers in inner city Birmingham schools and many have to request special arrangements around school absence for Eid al-Fitr. I wonder how many of your students hide or play down their religious beliefs?

9. Colonialism

‘Colonialism represents a legacy of suffering and destruction where one country assumes control over another by establishing colonies’ (p49). My recent trip to Canada showed an increased awareness and respect for indigenous populations where they are now collectively referred to as ‘first nations’ and often at International conferences you will now hear lecturers paying tribute to the original inhabitants of where they now call home. Lynch et al. highlight how Australia and New Zealand are leading the way when it comes to decolonising PE to ensure sports and activities on the curriculum better represent all cultures (p50). What are you doing to ensure activities and approaches to delivery of PE in your school are culturally appropriate?

Part II: Enacting social justice in Physical Education and Youth Sport

The second half of the book provides an opportunity to dive into ways of creating PE and youth sport spaces that are more ‘equitable, democratic, negotiated, inclusive, fair, self-affirming’ and focused on belonging. We are reminded to think about ‘pedagogy, environment, learning and assessment’ (p55) when it comes to social justice. Adams (2010) principles of social justice practice are cleverly unpicked with PE examples for:

- Balancing emotional and cognitive elements of learning

- Explicit teaching about social injustice

- Importance of community context

- Student-centred learning that is highly reflective and self-critical

- Valuing awareness and personal growth

- Acknowledging and seeking to transform power and privilege from white male superiority

A great table is provided on page 58 with ideas around how to set up the environment, learning focus, pedagogies utilised and forms of assessment that I encourage you to navigate to. We will now do a very quick whistle stop tour of some of the points made in the remaining chapters on ‘trauma informed pedagogies, democratic pedagogies, decolonising pedagogies, lifetime pedagogies, activist approaches, critical pedagogies of affect, and pedagogies of self-preservation’ (p59).

10. Trauma-informed pedagogies

We are reminded that ‘trauma can be a short- or long-term emotional response to a stressful or disturbing occurrence. Examples include bullying, physical or emotional abuse, rape, neglect, grief, poverty, war, discrimination, etc’ (p60). Often we see off-task behaviours in school and fail to navigate to the root cause rather than the visible symptom. We must all strive for ‘harm-free PE’ and broader experiences within school – as you know my mantra for a while now has been to help PE stand for Positive Experiences and that requires real commitment, criticality and ongoing reflection.

This second half of the book is really brought to life with case study examples of best practice like the one by Rachel Kelly from St Augustine’s CE High School in London who explains their approaches to help deescalate situations when students are having a crisis. We must take responsibility and seek restorative opportunities to best support our students. When was the last time you got out in the local community of your school to better understand your context?

11. Democratic pedagogies in PE and Youth Sport

‘When a democratic approach is taken, young people’s voices, choices, responsibilities, and negotiation skills, are harnessed’ (p66) to ensure the curriculum offer is fit for purpose for the local context of the school and particular cohorts within it. Asking big questions is considered a more democratic approach than setting learning objectives for each lesson. For example, what skills are required to work effectively as a team? A lot of the Girls Active research I have been involved with through Youth Sport Trust concurs with this notion of democratic programme design and I saw a lovely example in one of my trainee teacher visits last year where each class had their own learning contract that had been negotiated with the group at the start of the academic year. Again, the importance of treating physical, cognitive, social and affective domains with equal importance is highlighted at the end of this chapter.

12. Decolonising PE and Youth Sport

Have you ever stopped to consider why you teach football, hockey, netball and rugby? Why do we discuss the Olympics rather than Indigenous Games and do your prioritise a medicalised approach to health? Chapter 12 will challenge you to reflect and consider ideas that have been adopted by other schools, for example New Trier High School in the USA who explore the Māori game of Tapuwae. This chapter also explores the notion of sport for development and peace (SDP) and challenged me to reflect on the idea of marginalised communities being helped or even ‘saved’ from oppression through sport (p80). How do you ensure all of your students feel respected and their identities/ cultures represented? Do you even know the traditions and backgrounds of all of your students?

13. Lifetime pedagogies: social change through curriculum

Lynch et al. are passionate about challenging traditional orientations and finding better ways to ensure all children enjoy ‘culturally appropriate’ opportunities to ‘move for a lifetime’ (p85). A great case study examines feminist empowerment through self-defence that helped with body confidence, feeling of safety and participation in sports activities ‘free from body shame and fear of being victimised’ (p87). How effectively do you explicitly connect the movement patterns you teach in PE with potential transfer to lifetime activities and even occupations? As someone who has recently published a GCSE PE textbook the points around using a range of images ensure diversity is appropriately represented is something I carefully considered. A final question raised in this chapter, how often do you take students out into their local community to experience sport and physical activity in authentic spaces? I know this is something Mo Jafar really championed as a Head of PE before moving into Higher Education at University of East London.

14. Activist approaches and Youth Sport

Chapter 14 highlights that ‘at the heart of activist approaches is a commitment to listening and responding to the needs and interests of a diverse population of young people’ (p94). When was the last time you conducted student voice surveys and how well did you pay attention to marginalised groups or those currently least enjoying their PE experience?

The following four steps to curriculum co-design are explained on pages 97-98:

| Step 1 | building relationships with young people – don’t assume it will be easy to get young people to speak up about their day-to-day barriers without building trust first |

| Step 2 | Identifying barriers to sport in the community – create a democratic space by asking food questions and listening well, ensuring every individual has a voice |

| Step 3 | Imagining alternative possibilities – consider and negotiate change |

| Step 4 | Working collaboratively to create alternatives – this is the first step in a longer term quest for social justice |

15. Critical pedagogies of affect in PE and Youth Sport

This chapter digs deeper into our embodied identities, the influence of emotions and affects on our actions as educators. These idea discussed in more detail by David Kirk in his recent publication reinforce the importance of co-creating knowledge with young people (p105). Do you struggle to share the power of decision making with students in your PE programme?

16. Pedagogies of self-preservation

Chapter 16 warns us of the resilience required by educators and by young people when stepping up to challenge the status quo. It can often feel like a very uphill battle to challenge practices, policies and beliefs. The idea of precarity and ‘sheer uncertainty on what is next’ (p109) touched upon alongside important messages to find “me time” to recharge. Shrehan shares a very personal story of burn-out through relentless pursuits to do anything for her students and colleagues, reminding us that to care for others we must first make time to love and care for ourselves. How effectively do you ‘put on your own oxygen mask before helping others’? (p117).

17. Wrap up: be the change

Reflecting on, questioning and challenging the status quo is a common theme throughout this book. Like me, you will likely need time and space to absorb and think critically about some of the notions shared in this book and how they make you feel. Lynch et al. remind us that ‘addressing social justice issues … is HARD’ (p119) but something I would suggest we are duty bound to do as responsible citizens. Perhaps the first question you need to ask yourself is around how well you really know your local context and what you could do better to amplify the voices of marginalised and unheard individuals? Real change is achieved at the chalk face and hence this movement needs you. What will you pledge to do today? Tomorrow?

Take-aways

It has been hard to capture all that is contained in this short book through five suggested take-aways for physical educators but here goes:

- Reflect on the traditions of your school and how well they represent today’s multi-cultural society and the local community that you serve

- Find ways to build trust, listen to, and amplify the thoughts, feelings and desires of margnialised individuals

- It is not good enough to challenge stereotypes when we hear them, we must be “anti-ism”

- Be careful with tokenistic approaches to raise awareness to disability or less colonised sports by offering more than isolated units or taster sessions

- Change requires us all to act now, with the stacking effect of many small steps made at the chalk face making a big difference

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this you may also enjoy the first in our ‘belonging in PE’ series of courses.

I also highly recommend taking a look at these open-source research papers:

- The A-Z of Social Justice Physical Education: Part 1

- The A-Z of Social Justice Physical Education: Part 2

Finally, here are links to a selection of our other book club reviews:

Responses