Teaching Sportsmanship and Gamesmanship in PE Lessons

Many PE teachers overtly teach sporting conduct including topics such as sportsmanship, gamesmanship and deviance. Furthermore, PE teachers often make reference to nuanced versions of these concepts such as fair play or etiquette and even types of deviance such as positive and negative deviance. For these reasons, I want to take this blog post as an opportunity to set the standard for teaching these concepts and to try to ensure that the PE teaching sector has a clear perspective on each concept.

The historical background to sportsmanship

Those of you who taught A-level PE over the past 10-20 years will have a solid understanding of the history of sportsmanship. You will have taught units on pre-industrial sport, the influence of the British public school system, the liberalising headmasters, the role of rational recreation and the birth and influence of the middle class. But I want to make a very quick run through the main points so that we all have it clear what sportsmanship is.

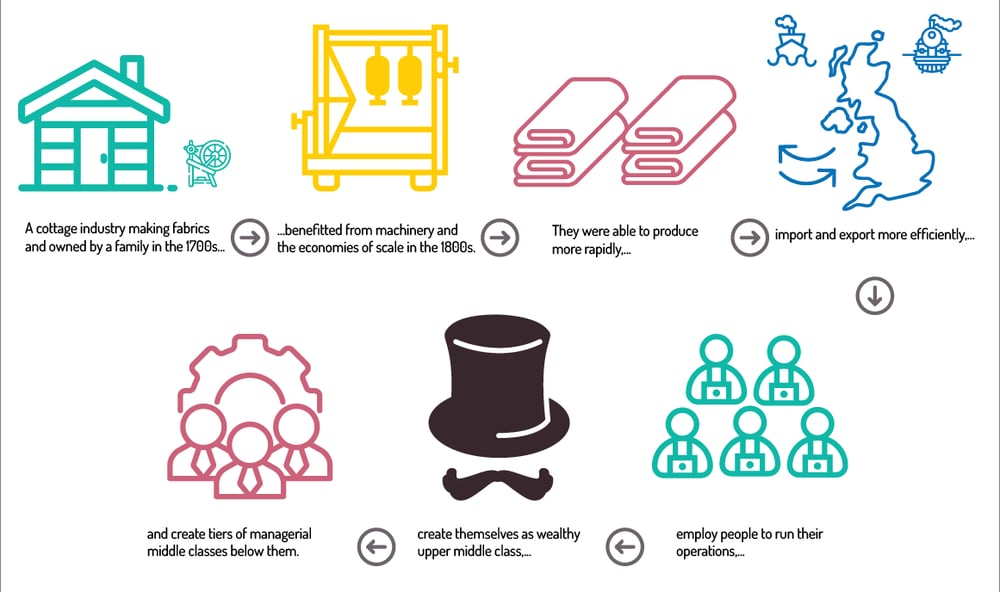

Sportsmanship is derived –broadly speaking– from a 19th-century middle-class interpretation of sport. The middle classes (an economic and societal group that had barely existed in pre-industrial times) came to prominence in Great Britain as a result of the Industrial Revolution. There are so many examples of this that a summary will always fall short but let me provide you with one example:

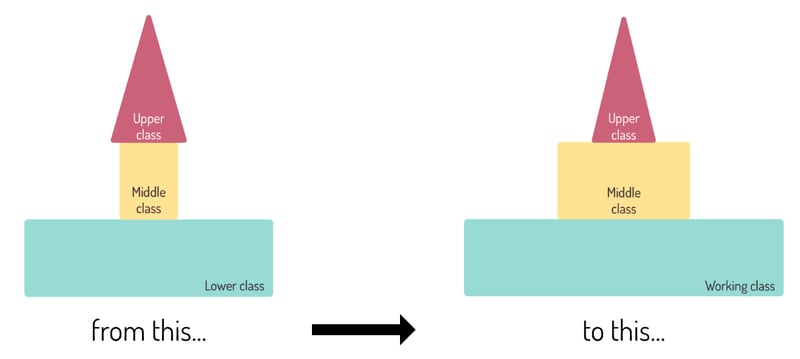

For reasons such as this, professional services in commerce, law and education were required and a whole tranche of professional classes emerged. These were the new middle class, with the nouveau riche (the original owners or new entrepreneurs) at the very top of this new intermediary structure. Essentially, society went:

There was a significantly bigger middle class but you may also notice that the lower class was “relabelled” and that it expanded too. There was a population explosion as people migrated to the cities.

So, we have a middle class and they are “new”. This “new middle class” lacked tradition and customs. So what did they do? They created them. Or, more accurately, they adopted them from the people they aspired to at the top of the pyramid.

The middle classes, now educated at endowed public schools, developed “rational” versions of traditional sports and went on to codify these sports by the mid to late 19th century. Association football, rugby, athletics, rowing, swimming and other sports now sat alongside previously established games like cricket as new expressions of middle-class “culture” and identity.

These new sports –it was argued by the middle classes– were played in the image of God and concepts like fair play and sportsmanship became inextricably linked with them. The middle classes believed that sport was respectable, fair, and non-violent and also that it developed honour, loyalty and courage and teamwork. If you find yourself aspiring to sportsmanship in the modern world, this is why. This is its origin.

As time progressed, sport diversified and games such as rugby and Association football became hyper-popular with the working classes too. But the working class, generally speaking, saw the world differently to their richer equivalents and saw sport as a vehicle for other things: for identity, for fun, for ritualism and, yes, for earning money. Therefore, the middle-class identity within sport was disparate from the working-class identity and this is clearly represented in “the schism” between rugby union and rugby league and also within sports such as swimming and athletics which, at times, banned “workers” from competition via their “exclusion clauses” which were, quite literally, class discrimination structures.

But the aspirational principle of sportsmanship lingered and does so today. A concept born out of the search for identity in the 19th century by the middle classes is seen today as what we should be striving for in modern sport.

Defining sportsmanship

The definition of sportsmanship is:

Fair and generous behaviour or treatment of others, especially in a sporting contest.

But if we break that down slightly, we can see that “fair” comes from playing and competing within the rules. We can see that “generous behaviour” comes from abiding by the spirit of sport. We can see that “treatment of others” is about respect for teammates, opponents, officials and coaches. Therefore, in practical terms, sportsmanship within sport itself is:

Abiding by the rules and spirit of the sport whilst always showing respect for other participants.

When you think of modern sport, and especially if you are an educator, it’s hard not to aspire to this. It feels “correct”, somehow. You will be educating about and through sportsmanship within almost all PE lessons. You may also find that sportsmanship is aspirational and “the way it should be”. Try to challenge your own thinking of this. Find the limits, in your own mind, of the space that sportsmanship occupies. For example, if you are watching “your team”, are you willing for them to show less sportsmanship in order to win or to score or to avoid defeat? In which situations do you accept that sportsmanship is not necessary? Have you ever competed and opted out of sportsmanship-type behaviours? If so, what caused this?

Sportsmanship is an intangible concept and all one can do is to “feel it”. It is nuanced and changeable but, despite this subjectivity, people know exactly when sportsmanship is not displayed. And, you know what? Except in the cases that I have discussed above, people generally detest a lack of sportsmanship.

Defining gamesmanship

Wikipedia defines gamesmanship as

the use of dubious (although not technically illegal) methods to win or gain a serious advantage in a game or sport

So, let’s break that down. Gamesmanship is:

- within the rules (remember this);

- focussed on winning; or

- focussed on gaining an advantage.

So, gamesmanship is even more nuanced than sportsmanship. But one thing is for sure: any act of breaking the rules is not gamesmanship. Therefore, all of the following will later be defined by something else and are NOT acts of gamesmanship:

- time wasting;

- faking an injury;

- simulating foul play/diving; and

- (in some sports) appealing for a referee’s decision.

None of these acts are examples of gamesmanship and I actually want to pause a moment to urge all PE teachers including exam writers and markers to NEVER accept these points as such. All of them are outside the rules of the game and are deviant in nature. More on this later.

But if I convert them into a legal act, they become gamesmanship:

Please, please, please educate your groups to be able to distinguish these concepts. If we don’t, students can never understand gamesmanship.

The win-ethic

Further down this post, I am going to discuss deviant behaviours in sport and, at that point, I will be writing about the win-at-all-costs mentality in sport. There is another concept, however, that sounds similar but is actually quite different: the win ethic. The win ethic is what leads to gamesmanship. The win ethic is the idea that…

winning is the ultimate expression of sport and that all legal behaviours should be manipulated to cause the greatest chance of winning.

We will all be comfortable with aspects of this concept. For example, if an athlete trains hard to compete and win, you will likely view this as positive. But what if the same athlete takes every performance-enhancing AND legal supplement and aid in order to maximise their chance of winning? Do you feel, likewise, positively about this action? These are interesting points because both stem from the win ethic.

Deviance in sport

The BBC defines deviance in sport as follows:

When a player, manager, spectator or anyone involved behaves in a way that knowingly breaks the rules or ethics of the sport.

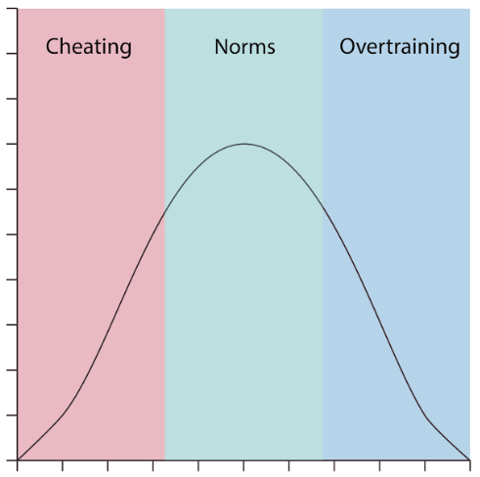

But I want to take this concept further. Whilst deviance is definitely deliberately breaking the rules, I would like to add a little nuance to the conversation. Take a look at this image:

The green section can be thought of as norms and these norms include BOTH sportsmanship and gamesmanship-based behaviours. One could argue that sportsmanship is, perhaps, the apex of the curve.

Now look at the red area of the distribution. This is known as negative deviance or cheating and behaviours such as doping, violence, match-fixing, gambling, faking, simulating, discriminating and so on exist in that space.

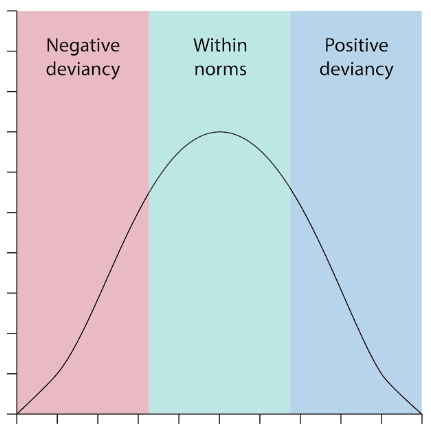

But there is a blue area too and we refer to this form of deviance as positive deviance. Positive deviance, titled “overtraining” on the graph occurs when an individual or team overapplies the norms of sport and takes them too far. Examples include fitness obsession, playing when injured or even putting one’s body in serious danger in order to compete or win or avoid defeat.

Therefore, deviance can be both positive and negative:

Interestingly, positive deviance, as well as negative, can be very dangerous including being the cause of injuries such as stress fractures or ligament or cartilage damage. As always, “finding the balance” is the best way to do things.

The win-at-all-costs mentality

This approach to sport is cynical, entirely negative and needs to be eradicated from sport. An athlete showing a win-at-all-costs approach will do anything to win. Anything! This is very different from a win ethic, which can be paraphrased as “doing anything legal to win”. Win-at-all-costs approaches always end badly. Whether a performer dopes, or attacks or fixes, this approach is harmful and has no place in sport now or in the future.

Final thoughts

Try to discuss these ideas with accuracy and nuance with your students. Don’t be afraid to challenge their ideas. Where possible, educate students about the historical background of sportsmanship and help them to understand why many people hold conflicting views on sportsmanship and might experience the classic *double-think position (stating that participating is more important than winning, whilst, moments later, screaming at a referee to award a penalty or free kick for their team). Sport, like people, is a nuanced concept and one that can help students shed light on their own perspectives and contradictions.

*double-think is a reference to George Orwell’s 1984 where it was the acceptance of contrary opinions or beliefs at the same time, especially as a result of (political) indoctrination. In sport, we can believe that sportsmanship is “right” but believe it is also acceptable to behave with gamesmanship in order to win.

I hope this has been a useful read.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)