Eight Things I will Never Say in a School

Allow me to introduce myself. I am James Simms, a PE and biology teacher who has dabbled with the teaching of MFL. I have taught full-time in five different state secondary schools and colleges in England and Wales over a 22 year career and have held positions such as PE Teacher, Course Manager, Head of PE, Assistant Director T&L and Assistant Heateacher.

Throughout my career, I have built excellent working relationships with the vast majority of my colleagues and with all students I have worked with. But I have also had the sense that my educational views and stances differ from others around me and that I am at times, the exception when it comes to educational thought and provision.

For this reason, I am going to write ten phrases that I will never use in an educational setting even though many colleagues and even students around me will use them commonly. I will also try to justify to you why I don’t use these phrases. I am writing this post not because I believe I am right or have all the information but because I want to challenge dominant thinking and give teachers a different perspective to that which might be common in PE offices and school staff rooms around the country.

You will never hear me say any of the following:

- High ability, medium ability, low ability. Ability in general.

- I need to cover the course.

- Teach to the spec. / Don’t worry, it’s not on the spec.

- Differentiation by task.

- Differentiation by outcome.

- It’s what Ofsted wants me to do.

- You don’t need to learn that for your exam.

- Knowledge organiser.

So let’s start with a biggy. I fundamentally reject the education system’s, school’s or even teacher’s assumption that it/they can know a student’s learning potential. Allow me to say this categorically: Neither you, the reader, nor I, the author, nor any teacher anywhere can know the learning potential of any other human being. Therefore, suggesting that a student or group is “High ability” is flawed. At best, teachers can know a student’s current performance and past performance levels. That’s it. Full-stop! Yet, up and down the land, teachers and educational systems make reference to ability in conversations and documentation.

To me, “ability” is a far more permanent state than performance. Performance can change almost instantaneously, whereas ability is more fixed. If we refer to students’ ability, we are basing our work on two fundamental flaws:

- That we are able to measure or estimate a student’s ability.

- That based on this imperfect measure/estimation, we can project at what level a student should learn.

Both of these assumptions are unfounded. I want to ask every reader a question:

Please, note the word ability specifically. Not performance level. Ability. It is my strong claim that none of us can do this and that any system or protocol based on “ability” should be challenged and, potentially, rejected.

In place of ability, please consider using the phrasing of “current performance level” or simply “performance”. Performance is a very temporary state and is based on learning behaviours such as concentration, engagement, interest and effort. These controllable factors are those that we should be working with in schools and colleges.

I have heard this phrase very commonly in schools. Teachers, understandably, feel that their responsibility is to “get through the course” or to “know I have told them”. This is a completely natural assumption based on everyone’s own school experience and a sense of professionalism. I genuinely understand this. However, my work in my classrooms has no relationship to “covering a course”. I see my responsibility differently. My responsibility is to cause the maximum depth and breadth of learning in skills and knowledge that are relevant to my students. “Covering” a course does not even come close to my responsibility. “Covering” a course would mean that, regardless of my students’ learning behaviours, I have “completed” my work. This is not how I see a classroom.

I also want to dwell on a nuanced point: “covering” a course is all about the teacher’s behaviour. It is about what the teacher has done. Not what the students have done. Given that learning is the currency of classrooms, I will not place emphasis on the teaching element other than when it causes learning.

I have previously written extensively on this topic (PE teachers, stop teaching "to the spec"!) so, for some of you, this will be repetition but I absolutely and outright the concept of teaching to a spec. In my opinion, “teaching to the spec” means:

This seems reasonable, doesn’t it? Well no, actually, it isn’t reasonable. I respect my students' right to learn the broadest range of knowledge and skills that is relevant to them. Furthermore, specifications are not the same as the mark schemes that exam courses are assessed by. Mark schemes are better described as:

This matters and teaching up to the level of specification content will never prepare a student to be able to apply and utilise that content in the ways required.

Therefore, my stance is different. My core responsibility to my students and minimum standard is:

I would urge teachers reading this to challenge me on this concept. Before doing so, please read PE teachers, stop teaching "to the spec"! for more details.

OK, this one is a biggy: I do not differentiate by task (or outcome - see next point). I’ve tried it many times and it is based on false assumptions. Therefore, I reject it as contraindicating or more harmful than helpful.

To accurately differentiate by task, a teacher needs to confidently understand the learning potential of their students. No teacher knows this. As stressed above, there is not a valid test in existence that measures a student’s learning potential. It doesn’t exist. Therefore, I will never again guess what my students' learning potentials are.

Beyond these points, I want you to consider what differentiation by task is subtly indicating to our students. It is saying, in my opinion, these two things:

- I know what you are capable of.

- There is a relationship between pace of learning and learning performance.

The second point is more subtle. Many teachers use differentiation by task because the “seat-time” allocated to a task is fixed. However, this forces time to be the limiting factor in students’ learning. But, and this is a big but, we know today that the pace of learning and what someone is capable of learning are not correlated unless an arbitrary time limit is applied to the learning episode. Therefore, differentiation by task is not only a false science but it is educating children to believe that they are “smart” or “dumb” based not on their learning capacity but on the potentially irrelevant variable of pace. Therefore, you will never hear me talk about differentiation by task nor allow it in a learning environment I am responsible for.

In many ways, this point leads on from the former. Just like differentiation by task, differentiation by outcome is flawed based on the teacher’s incapability to accurately judge the best potential outcome for any learner. This is not a criticism of teachers. It is merely the acknowledgement of reality.

So, how should one differentiate if not by task or outcome? Well, different authors will have their own views on this but my approaches are as follows…

The only valid forms of differentiation that I advocate for and structure into my learning environments are:

- Differentiation by pace;

- Differentiation by repetition;

- Differentiation by types (not quantity) of scaffolding.

Let’s take pace. If a teacher sets a “ten-minute task”, this is guaranteeing a variable outcome. Why? Because:

But, if we change this relationship, something very interesting happens:

In other words, the expectation for every task is mastery but different students can achieve this at different rates. Now, when I discuss this with teachers, the conversation often goes into one of a few directions. Sometimes I am asked about students waiting for one another: this is only necessary if the following task has a fixed seat-time. Sometimes teachers worry students will not “complete” their courses: this is only the case if all students follow the fixed seat-time model. Other teachers worry that different students will be at the different points in the course: this is only an issue if the course is linearly structured.

So, whilst I am only touching on these concepts here, I do want to challenge you to consider that, perhaps, the course structures that we all take for granted are founded on fundamentally flawed assumptions and can be challenged.

Ok, I feel a bit bad about this one because it will cause conflict in colleagues’ thinking but I want to make a very clear statement: “I do not care and have not ever cared what Ofsted think of me, my teaching and my departments”. Now, this doesn’t mean that I am not aware of Ofsted’s publications, frameworks and advocations, I am. I read all of them and, sometimes, I read something that challenges me. When this happens, I ponder that idea and, if it is impactful, I apply it. However, what I will not do ever, is use an Ofsted framework as my framework. Let me give you an example:

In recent years, “curriculum intent” has become quite buzzy because it has been referenced by Ofsted. But for this to have an impact on me, my team and our processes, I would need not to know why we do what we do, how we do what we do or, indeed, what we do. That is all it is, really. Why do you do what you do? How you do what you do? What is it you do? Therefore, Ofsted is irrelevant to me because these factors have been considered. They dwell in every behaviour.

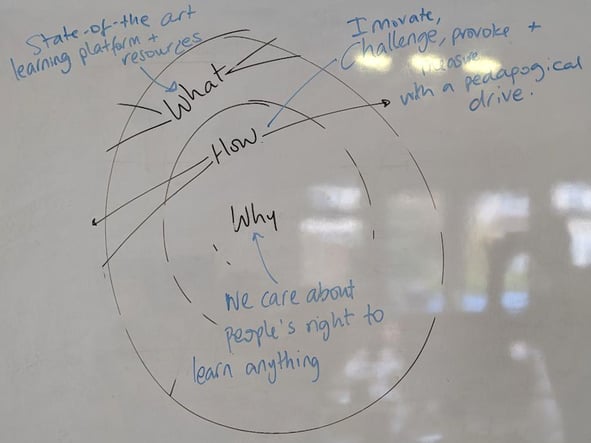

Now, to bring this to life a little, I want to share some work that we do at The EverLearner Ltd. It is based on a really interesting model called the 3-hour brand sprint and I would encourage PE departments to consider running it if time allows.

This was one of the outcomes of our recent work at The EverLearner Ltd covering our Why? How? and What?

Our three hour brand-sprint

Our three hour brand-sprint

- So our "Why?" is: “We care about people’s right to learn anything.”

- ...our "How?" is: ”We innovate, challenge, provoke and measure with a pedagogical drive.” †

- ...and our "What?" is: “We provide a state-of-the-art learning platform with additional resources.”

† We have recently updated this to “We innovate, challenge, provoke, measure and report with a pedagogical drive.”

Furthermore, we undertake this work, as well as the entirety of the brand sprint, every 6 months with our entire time. Therefore, our "Why?", as well as our "How?" and "What?", are clear to everyone and everything we do.

It is not uncommon for students to utter this statement. I do not. If a student asks me a question, I answer it. Sometimes I have to manage how time is managed in order to answer the question but I always answer it.

It happens, as far as I can tell, in the following scenarios:

- A student has asked a teacher a question but the answer to that question is considered by the teacher to be off-spec.

- Specifically, a student has asked a question that is from the next level of PE study.

- Specifically, a student has asked a question which relates to a model of learning from biology/chemistry/food science that is taught “differently” in PE.

- One educator (let’s say within a department) has taught students an idea and another educator has come across this idea when teaching the same students.

- Students have been guided by one educator who has taught to the fullest extent of the mark scheme (argument 1) and another teacher is teaching up to the spec.

So, let’s make this clear: You, I or any teacher does not have the right to tell a student “You don’t need to learn that.” Writing philosophically, students may choose to learn anything they wish and our role is to guide and support them. Now, I am unlikely to give classroom time to a more abstract idea or low-impact concept but I will never - and I really mean never - tell a student not to learn something. Rather, I may use phrasing like this:

- “Great question and, if there’s time left at the end, I’ll answer it for you. But, for now, I want us to stay focussed on…”

- “The answer is… but I want you to be aware that you won’t be examined on that.”

- “Fascinating question. I have some resources on that which I can share with you and you can look at it in your own time.”

And my personal favourites:

- “Fascinating. You’re right. In biology it is stated that… but in PE we learn the same thing in this way… What do you think?”

- “Right, stop what you’re doing, class. Student X has just asked me a question but it relates to A-level rather than GCSE PE (say). For those of you interested, I’ll teach this for a few moments over here (part of the room, say). Just be aware this won’t be on your exam this summer and if you’re up against it to get your tasks mastered, you might want to stay with that.”

This list is not exhaustive, of course, and you may find your own ways to answer this but notice what I am doing with all of those responses. I am both:

- honouring the student’s right to be intrigued by or learn something they are interested in; and

- remaining focussed on the job in hand, which is students mastering the fullest breadth of our courses as a minimum.

I believe that this is exemplary practice and I urge you to do likewise.

I can’t stand knowledge organisers. I mean, I can’t stand them. As far as I can tell, a “knowledge organiser” is a piece of work that is completed by a teacher and handed to a group of students so that they have a comprehensive guide to all the learning required on a course. I want to ask a question:

Why would any educator do this?

I’m serious, why do educators do this? Here are some other questions:

- If an educator’s role is to cause the deepest and broadest learning possible in a skill-set, why would they work on this and hand it to a student?

- How does it cause the deepest and broadest learning?

- Why is the opportunity to create this document taken away from the learner?

I do understand that teachers want to ensure that crucial information is in the hands of students, but this practice and the message it provides is very negative.

So, there you have it, eight things I will never use in a school. I am hyper aware that not everyone will agree with me, that’s fine. Disagreeing is good as long as we discuss and find common ground in a supportive environment. Do be encouraged to challenge me.

Thank you for reading and have a lovely day.

James

%20Text%20(Violet).png)