Johnny Cooney Interview: 20 Years in the National League

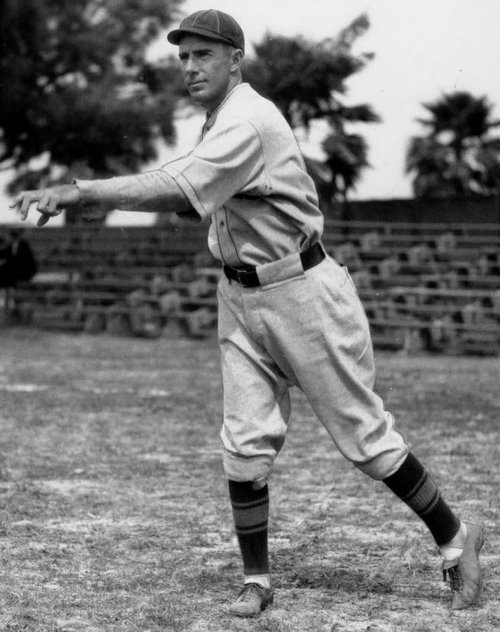

Johnny Cooney - a left handed pitcher forced to move the outfield through injury

Norman L. Macht interviews pitcher turned outfielder Johnny Cooney and his wife about playing in the National League.

A career .286-hitting left-handed pitcher whose arm problems forced him to become an outfielder, Johnny Cooney had a 20-year big-league career as a player with the Boston Braves and Brooklyn Dodgers between 1921 and 1944, followed by 18 more as a coach with Boston/Milwaukee and the White Sox (1946-1964}.

He and his brother, Jimmy, were together on the 1928 Braves.

We were joined by Cooney’s wife, Alice, at their home in Sarasota, Florida, in the fall of 1985 - Norman L. Macht

Johnny Cooney: The Early Years

I was born in Cranston, Rhode Island. I’d go on weekends to pitch for a semipro team in Willimantic. The catcher and manager was an old-timer named Ed McGinley.

One day in September 1920, I pitched a six-hitter against the Braves in an exhibition game. A Red Sox scout was in the stands and he asked me to come to Boston and sign.

McGinley says, “I’ll go with you. I’ll be your agent.” So we went to the Red Sox office. Ed Barrow was the manager. McGinley and I go into the office and I said, “I have an agent.”

A group of Chicago White Sox coaches, including Johnny Cooney

“An agent!” he says. He pulls out a contract and says, “We’ll give you $500 to sign and $300 a month.”

He starts writing out a check. Mr. McGinley says, “No check. We want cash.”

Barrow blew up. “What, you wouldn’t take a check from the Red Sox? Get out of this office.”

We left and sat on a bench in Boston Common and McGinley says, “Maybe we shoulda taken that check.”

Signing for the Boston Braves

A few days later a Braves player came to see me and asked me to sign with them. This time I went by myself. I got $500 and $400 a month. I still had to give McGinley $250.

I joined the team in New York for the last few weeks of the season. First time I’d ever been out of Cranston. We took the overnight train and arrived about seven o’clock in the morning.

I’m standing there looking lost and along comes the Braves shortstop, Rabbit Maranville.

“What’s the matter, kid. You lost?”

“Yeah.”

“Come on with us.”

We get in a taxi and out comes a whiskey bottle. “Want a drink, kid?”

“No thanks.”

Seven in the morning and Rabbit’s already drinking. Welcome to the big leagues. I never drank, smoked or chewed tobacco.

George Stallings was the manager. He didn’t wear a uniform, looked like a minister. First day I’m sitting near him. A spitballer, Dana Fillingim, was pitching. He always wore expensive hats. This day he was wild.

Stallings said, “Look at him. A ten dollar hat and a ten cent head.” I’d start the game near him, but by the end I’d be down the end of the dugout. I never heard so much cussing in my life.

After a few weeks in 1922, I went down to New Haven, where I was 19-3 when I was recalled in September and stayed through 1930.

By 1925 I was among the best lefthanders in the league: 14-14 with 20 complete games. Then my arm went bad. Chipped bones in the elbow.

The First Elbow Operation

My first operation left the arm paralyzed, and crooked. For three months they tried to straighten it electrically and put me on a stretching machine in a New York hospital, a 250-pound pull.

I got out of there and first thing the arm bent up again. Three months later another x-ray showed a bone block on the inside of the elbow Locked all the time. They chiseled those off.

By that time my arm was two and a half inches shorter. It took my fastball away. I was a utility man from 1927-1930, went back to the minors at Toledo in 1931, then Indianapolis for four years, and hit .375 in 1935.

Ballplayers make the manager.

Rogers Hornsby managed the Braves in 1928. George Sisler was near the end of his Hall of Fame career.

One day Hornsby sent me in to run for Sisler, the first time he had ever been taken out of the lineup. He was so mad, he and Hornsby almost came to blows in the clubhouse. But Sisler was a real gentleman, very quiet.

We finished seventh with a 60-103 record. The club owner, Judge Emil Fuchs, figured he couldn’t do any worse, so he became the manager. He knew nothing about baseball.

A genial guy, he’d sit on the bench telling stories. One day a batter had a 3-1 count on him and he looks in to the bench for a hit or take sign and Fuchs sat there and did nothing.

Finally, the third base coach called time and came over and asked, “What do you want him to do?” Fuchs looked at him and said, “Tell him to hit a home run.”

We had a pitcher, Socks Seibold, who didn’t like Fuchs. Refused to sit on the bench with him, He sat alongside the dugout.

When Fuchs wanted Socks to go in to pitch, he’d tell a coach, “Tell Socks to go down to the bullpen and warm up.” Socks would say, “You tell the judge I’m not going down to the bullpen.”

We finished last, but with Judge Fuchs managing, we won six more games than we did under Hornsby.

Playing for Casey Stengel

I played for Casey Stengel four different times over seven years, at Toledo and Kansas City in the minors and Brooklyn and Boston in the majors. Casey knew his baseball. In Toledo, they didn’t have much money.

Once, when payday was coming up, Casey had a team meeting. “Boys,” he said, “decide what you think you’re worth and we’ll write it on a card and pin it on your back and we’ll have an auction to meet the payroll.”

In 1931 I took my regular turn pitching and played in 113 games for Toledo. I’m in right field one day in St. Paul. The second baseman made two or three errors in a row.

Casey pulled him out and brought me – a lefthander – in to play second base.

Another time in St. Paul they got seven runs in the first inning. The first two Toledo hitters went after the first pitch and Casey went wild. “From now on everybody takes two strikes,” he yelled.

Along about the fifth inning, the St Paul pitcher caught on and began to throw the first two pitches right over the plate. In the sixth inning, Casey put me in to hit and said, “Don’t take two strikes.” I hit the first pitch on the roof.

Stengel brought me to Brooklyn in ’36, and at the end of ’37, I was traded to St. Louis with three other players for Leo Durocher. Branch Rickey was the GM at St. Louis.

He wanted me to go down to Columbus. I was a ten-year man and said no. Came opening day, Rickey says, “I’ll give you $7,500 to go to Columbus and be the manager.” I said, “Mr. Rickey, I don’t want to manage and I don’t want to go to Columbus.”

So he gave me my release. I could have collected ten days’ pay from him because they didn’t give me any notice. But I already had a job with Stengel, who was now the Boston Bees’ manager.

I was almost electrocuted one night in Jersey City. They had just put the lights in and they ran the cables inside the fence. It was damp, the grass was wet.

A ball was hit along the fence. I came in and my spikes cut through the wire and gave me a shock. The next day they put the cables outside the fence.

The Dodgers

I was with Boston for five years, second in the NL in hitting 1939-1940. End of ’42 they released me. Ted McGrew, a Brooklyn scout, called and offered me a job with the Dodgers. And who is the general manager there now? Branch Rickey.

They released me in the middle of the 1944 season. Joe McCarthy of the Yankees called me. What was I getting paid? I said, “$9,000.”

“Oh, we can’t pay you that kind of money. I’ll talk to Ed Barrow.” Barrow was the Yankees’ general manager.

Now, twenty-five years after he had thrown me and McGinley out of his office in Boston, I’m dealing with Ed Barrow again.

I said, “You probably don’t remember this, but twenty-five years ago you kicked me out of the office in Boston.” He laughed. He gave me what I wanted. But they released me in August.

Then I got a call from Burleigh Grimes, who was managing in Toronto. Grimes had been a tough pitcher, who would throw at you and if you didn’t like it, you’d go down again.

He wanted me to play for him, so I went with the understanding that I’d get my release at the end of the regular season, before any playoffs. When I got there, I found that he was going to be my roommate.

My son was in the Navy about to ship out, so I left the team as agreed before the playoffs to go see him. I got a notice from the minor league office that I had deserted the team.

I wrote to them and explained and never heard any more about it.

Now it’s 1945 and I’m 44 and Casey Stengel is managing at Kansas City and they’re at the bottom and need help, so I go with no spring training and I run into a few doubleheaders and a three-week road trip, hit .343 for them, and a pitcher hit me and broke two ribs and that was the end of my playing days.

Casey went to Oakland and wanted me to go with him as a coach. But Billy Southworth took over the Braves and offered me a three-year contract as a coach, so I took it.

Otherwise, I would have wound up with the Yankees when Casey took over there in 1949.

Southworth was very strict. In spring training in Bradenton, he would put little toothpicks on top of the doors of the players’ rooms.

He’d come back later and, if the toothpick was gone, he knew you’d gone out or come in late. He’d have the little clubhouse man, Shorty, sit out front of the hotel to see who came in late. We won the pennant in 1948 and I got a World Series check.

I managed briefly, filling in for Southworth for a couple of months in 1949. I even umpired once – for two innings in 1941. In those days the umpires took a boat from New York to Boston.

We were playing Brooklyn and the boat the umps were on was fogbound and late arriving. I was designated the home plate umpire, but I stood behind the pitcher and called the balls and strikes.

After two innings, the umpires showed up.

Alice Cooney on her life in baseball

Alice: I grew up in baseball. My father managed the Albany team for quite a while. He also umpired. But I never dreamed I’d marry a ballplayer.

The wives were not allowed to go to spring training. We got along beautifully. I loved it. We dressed up – hats, gloves, the works to go to the games. Now they look like they’re at the beach.

I think it’s terrible the way the fans dress. You could pick out a ballplayer in a crowd by the way they dressed and looked. Today they look like tramps and need haircuts and shaves.

One time in Boston one of the wives wore slacks. She was told by the front office not to wear them again. After a game, we’d go for lobster dinners in Boston.

When the team was on the road the wives would go out to dinner, play bridge. I never missed a game. We had one boy and would rent an apartment.

We spent the winters in Sarasota. When school was out we’d pack up the car and away we’d go. It was a nice life. I think it was a wonderful time. I enjoyed every moment of it. I wish we could go back.

I didn’t like night baseball. It interrupted your whole living schedule. It was terrible. In the old days, you couldn’t find an open place to eat after a night game. And if you did, you couldn’t go to sleep afterwards.