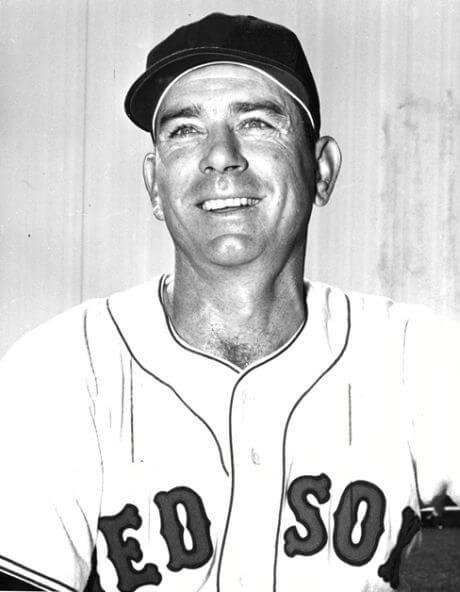

The Story of the Incredible, Arnold “Mickey” Owen

Arnold “Mickey” Owen is one of those star-crossed ballplayers remembered for one ignominious moment out of a long career.

But there is more to the story of his 13 years with the Cardinals, Dodgers, Cubs and Red Sox, plus another 4 ½ in the Mexican League, beginning in 1937, than that notorious passed ball in the 1941 World Series.

In his hotel room the morning after playing in an old-timers game in Pittsburgh in June 1990, Owen, a knowledgeable student of baseball history going back to 1840, and analyst of stats by decades, described the World Series incident and predicted the coming of 10-year, $100 million contracts for superstars.- Norman L. Macht

Owen’s early life

I was born in Nixa, Missouri, in 1916, but moved to Los Angeles with my mother and stepdad when I was seven.

My stepdad, a navy man, died young, and my mother sold insurance and real estate and we lived behind the office.

I made money with a paper route and as a professional marbles shark, won all the other kids’ marbles and lunch money until the mothers came to school to complain and they stopped me.

Mickey Owen's start in baseball

I learned baseball at the Hoover Street playground. I was a shortstop and the second baseman was Bobby Doerr.

Later we got to the Western regional finals of American Legion ball but got beat. Doerr and two others from that team were signed, but nobody wanted me as a shortstop.

A Cardinals scout, John Angel, told me they had orders to sign catchers. I could throw pretty good, but I said, “I don’t have a catcher’s mitt.”

So he gave me one as a bonus and I became a catcher. Signed for $125 a month. This was 1935.

I went to spring training in Houston. There were 35 players there – three of them catchers. One had a sore arm, and couldn’t throw across the room.

One was 5-foot-8 and weighed about 245 pounds. So I got to do a lot of catching. They sent me to Springfield in the Western Association.

Baseball legend Mickey Owen

Eight games a week – every day and two on Sunday. I hit about .310

The next year I went to Columbus in the American Association. They didn’t have any catchers, so they started me and I hit pretty good.

Up until then, I had always been called Arnie.

The Columbus manager, Burt Shotton, pinned the name ‘Mickey’ on me because I had big ears like Mickey Cochrane, and I was fiery.

I made the Cardinals in 1937 but didn’t play much. I remember catching Dizzy Dean.

You know how a jockey can make a horse run fast or slow? Dean was the greatest at changing the pace at which he worked.

Then all those great young pitchers came up from the Cards’ farm system – and along with them came catcher Walker Cooper and I knew I was dispensable.

Getting traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers

I had never lived up to what they expected. In December 1940 they traded me to Brooklyn.

The Dodgers had some mean pitchers – when they were on the mound.

All you had to do was tell Whitlow Wyatt he was pitching today and he’d turn mad.

One day he’s pitching and a fight broke out. A real brawl. I sat it out. I was too little. Wyatt says to me, “Those guys ought to put that much energy into getting me some runs.”

Johnny Allen and his famous temper

Pitcher Johnny Allen was a highly intelligent man with one of the worst tempers I ever saw.

Raised in an orphanage, he had been abused, kicked around pretty good. He hated some people, Bill Werber for example. Hated Werber with a passion.

He’d throw four straight at him, aiming right for the chest. I said to him, “Why do you do that? You only make it tough on yourself.”

He said, “When I was in the orphanage, there was one person who gave me a rough time, and he reminds me of him, and when I see him I remember that so-and-so. I’m getting even with him.”

Larry French

Larry French was another highly intelligent pitcher, but not angry. He had a good fastball and screwball, but when he lost his fastball, his screwball was not as good.

One thing about pitchers: they believe they still have the good fastball even when they no longer have it. They were creaming his.

So we’re sitting in the bullpen and he says, “I’m going to work on a new pitch.” He came up with a one-finger knuckleball but he wasn’t sure he could control it.

A couple days later he came in to pitch and I gave him a sign for that knuckler. He says, “I’m not ready.” I said, “Let’s find out.”

I was not about to call for any fastballs. It worked. He was 15-4 before he went into the navy as a captain.

[In the 1940s, pitchers who would come to be called closers came in as early as the fifth inning with the intention of finishing the game.

Hugh Casey was the best of his time. In 1941 he combined 18 starts (4 complete games) and 27 relief appearances, of which he finished 21.

He relieved three times in the five-game 1941 World Series. The Yankees led 2 games to 1 on Sunday, October 5, at Ebbets Field.]

In those days a lot of teams were good at reading catchers’ signs. Hugh Casey absolutely didn’t want anybody getting his signs.

He’d throw at you if he thought you were getting them. And he would never throw a change of pace. He believed even a poor hitter could hit it.

He had two good fastballs and two good curves.

One fastball was across the seams, a riding fastball, and the other with the seams and he’d give it a snap and let fire.

His curves – he had a hard quick curve, not a slider, wouldn’t break a lot and he could throw it hard. Then he had that big curve that – shoom! – broke like that.

He could throw either curve on the curveball sign and either fastball on the fastball sign.

I didn’t know which curve he would throw; I just had to be ready for either one. And I didn’t know which fastball he was going to throw.

That way the other team couldn’t pick it up either. All season long we used that system and never had any problems.

So he comes in to relieve [in the fifth inning, the Yankees leading, 3-2].

First pitch he tried to roll off his big curve and it didn’t break, just hung outside.

Ball 1. Next he tried the same curve, same result. Ball 2. From that time on I give him the curve sign and he throws that tight one and they couldn’t touch it.

So we go into the ninth inning [leading, 4-3] and hell, I’ve got a one-track mind anyway, so with two outs and nobody on and two strikes on Tommy Henrich, I give him the curve sign expecting that tight one and he throws that big one, and it broke – shoom! – like that and Henrich swings and misses and I’m late getting my glove down and it got by me.

[Henrich reached first on the passed ball. The Yankees went on to score 4 runs and, the next day, won the Series.]

Funny thing about it: the Guinness book of records people sent three of us certificates because the three people who were the best at what they did absolutely failed miserably all at the same time.

The reliever with the highest winning percentage lost the game; the ”Old Reliable” hitter struck out; and the catcher in the middle of setting the National League record for consecutive chances without an error missed the ball.

Playing ball in the Mexican League

I went into the service and then went to the Mexican League along with about twenty other major leaguers. I managed the Vera Cruz club in Mexico City.

Some fans carried guns down there for protection. Only once did I run for my life.

Babe Ruth came down for an exhibition game. Ruth was an old man and that high altitude got him.

Things get a little heated

I was catching one of the best Mexican pitchers, Ramon Brigande, an overhand fastball pitcher with a hard-to-follow delivery.

Babe was up there and he couldn’t hit one out of the park. That pitcher was zinging it in and Babe just fouled ‘em off.

The manager of Ruth’s team came out and said to the pitcher, “Why don’t you let the batting practice pitcher come out and pitch to Babe?” Brigande said, “No.”

They got into an argument and the pitcher shoved the manager in front of all those people and our club owner came out and told the pitcher to sit down and they put the batting practice pitcher in and he was laying them in there and Babe hit one into the bleachers and the people went wild. We thought it was all over.

We had a dressing room under the stands and there were three players in there: myself, the pitcher Brigande, and Danny Gardella.

This 14-year-old clubhouse boy comes in and he’s the brother of the manager who got shoved and he’s got a pistol and says, “Brigande” and Brigande makes a rude gesture to him.

We’re in the corner of the room and there’s a wall about six feet up and a three-foot space between it and the stands for cooling and we heard some people talking to the clubhouse boy in Spanish through the door trying to stop him from killing Brigande and we went over that wall.

Looking back at his career

I came back to Brooklyn in 1949 and a week later they sold me to the Cubs.

I was disappointed that I wasn’t a better ballplayer than I was. I don’t believe I was as good as I could have been. Nobody’s fault but my own.

My mother saw me play once, in an old-timers game in San Diego. At those games I always got a dozen balls and had them signed to give to friends.

I put her in the stands and asked the people around her to watch her, she was pretty old, and they said they’d take care of her.

After I got the balls signed I took them up to her to hold onto them.

When I came up to bat, Satchel Paige was pitching. I hit one against the fence with the bases loaded, almost went out of the park.

My mother was saying, “That’s my son” and hugging everybody. She was.so happy she started passing out the signed balls.

When I got back to her, she didn’t have a single ball left in the box. Six of the people around her gave them back to me.

Back in Missouri I was elected sheriff in the third largest county in the state, served 15 years, had 75 deputies.

My son and I plan to go into the memorabilia business, authenticating things, representing players who want to sell stuff.

I sincerely believe that when you have a great player he will be so valuable you don’t want to lose him.

I predict that within the decade of the 1990s there will be players who will get $100 million contracts for 10 years because the owners don’t want to lose that name.

They’ll have the players insured against breaking down.

Worldwide TV marketing is where the money will be. That’s not too much when you look at how many people they are selling that Budweiser beer to.