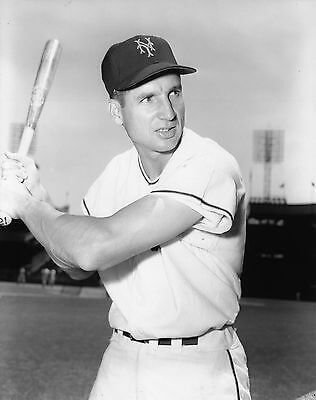

Bobby Thomson and the "Shot Heard Round the World” - his career his own words

Bob (“Call me Bob; I’m too old to be called Bobby”) Thomson is best remembered for hitting the most dramatic home run in baseball history – his 1951 “shot heard round the world” that turned an imminent Brooklyn Dodgers’ pennant-winning playoff game into a New York Giants miraculous comeback victory.

The third baseman/outfielder’s 15-year career (1946-1960) included four years with the Milwaukee Braves and two with the Cubs.

Forty-one years after he was struck by the lightning bolt of fame, we sat in the living room of his comfortable suburban home in Watchung, New Jersey. We talked about his life leading up to that moment, and his thoughts during that climactic time at bat - Norman L. Macht

Bobby Thomson’s Early Life

I was born in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1923, the youngest of six children. My eldest sister, Jean, was 11. We lived in an area my mother called Toon Heath.

As a girl my mother worked in a bakery. She was a plain cook but a wonderful baker of “sweets.”

We were quite poor. Before I was born, my father decided he was going to move the family to America.

When you stop to consider the substance of those people back then, making those decisions just to pick up and go to a new country made me admire and respect my dad very much. I lost him at an early age, 47.

Back then you had to apply to come over here and there was a long waiting list. He had a number, and wouldn’t you know, my mother was expecting me when his number came up.

So he had to make a decision whether to wait until after I was born and get back on the end of the line. He decided to get started and took off by himself, a decision I wonder if I could make today.

He was a cabinetmaker and had a tough time over here, sometimes out of work. He had to make enough money to live on, save for our passage, and send money home to support us.

There were a couple times he wavered and thought he might not make it. But he survived and we made it. I was two and a half when we made the voyage. I had never seen him until we arrived.

We looked like typical Scottish kids of the time. I had a woollen scarf around my neck and a cap.

Becoming a Baseball Fan as a Kid

We lived on Staten Island in New York. My dad had taken to baseball and became a Dodgers fan.

The rationale was that we had a tough time when we came over here and the Dodgers were called the Bums and they were always losing and I wonder if he related to that.

The Giants and Yankees were much more successful at that time. When I was seven or eight we’d walk a couple miles on Sundays just to see a sandlot game on Staten Island.

My dad took me to a couple games at Ebbets Field when I was about 11 or 12. His favorite player was Dolph Camilli, a strong man playing first base for Brooklyn.

My dad was not a demonstrative person, and didn’t have much to say. One day Camilli hit a home run and my dad jumped up and put his arms in the air – I’ll never forget that –and it was a wonderful thing.

I was always proud of him.

Later I had the opportunity to meet Dolph Camilli at an old-timers game in California, I really got a kick out of telling him that he was my dad’s favorite player.

How I started playing baseball

I had an older brother who played ball and got me started playing. My brother rooted for the Yankees. I don’t know what got me started as a Giants fan.

In high school, I was an infielder and worked out a few times with the Giants at the Polo Grounds, but apparently, they weren’t interested in me.

I worked out more at Ebbets Field with the Dodgers, and even played with a team called the Dodger Rookies. Now I’m getting out of high school and realize I’m going to sign a contract.

The Dodgers told me, “Please talk to us before you sign. We’ll better anything the Giants offer you.” But I never had any intention to sign with any team other than the Giants.

There was mutual hatred between Giants and Dodgers fans. I was a loyal Giants fan and was never going to sign with Brooklyn.

Playing for the Giants

The Giants sent me to Bristol, Virginia. I was just out of high school, a scared little kid, wet behind the ears.

I remember there was a fan in the stands, a big, fat, leather-lunged woman – scared the heck out of me. They had a good team, a good third baseman.

I just sat and didn’t play much. Bill Terry was in the Giants’ front office. He wanted me to be playing and I was shipped to Rocky Mount, North Carolina, and got into about 25 games.

I lived in a rooming house with four guys in one huge room. The clubhouse was very tight, had two showers.

The old bus we rode had the worst looking tires I’d ever seen. There were no windows in the last two rows of seats. One trip was 150 miles and on that bus it seemed like a thousand miles.

We stuffed our uniforms and gear and stuff into our uniform pants legs and pulled the belt tight and carried them on the bus.

The aftermath of Bobby Thompson’s “Shot Heard Round the World”

After a hot, sweaty game, we’d stuff those wet uniforms in the back of the bus.

As a rookie, that’s where I ended up. It got kind of chilly at night coming home. I used to lie on top of those sweaty old uniforms to help me keep warm.

I was such an immature youngster, it was just a way of life. Why do you become a ballplayer? You love to play baseball.

You don’t make an overnight decision, it just comes on you gradually, and it’s just something that’s there, like following a star in the sky. I had nothing else in my mind but being a ballplayer.

My Time in the Army Air Force

I was drafted into the Army Air Force in late 1942 and never left the U. S. I began training as a radio operator and that was killing me, so I applied for air cadets and wound up in bombardier school.

In advanced training I got an ear infection that put me in the hospital for a month and was pushed back one class. My original class went overseas.

We were ready to ship out when they dropped the A-bomb and our orders were cancelled.

I always had my glove with me. We’d play catch occasionally, and they’d throw grounders at me.

One night our barracks caught fire and we all ended up out in the street and there I stood with whatever I was wearing and my baseball glove on my hand.

Jersey City

In 1946 the Giants sent all their returning servicemen to their AAA Jersey City spring training camp in Jacksonville. There were hundreds of us there.

I expected to go back to Bristol and I didn’t look forward to going back and listening to that fat lady with the leather lungs.

We had races and I won them all and the Giants decided my speed was wasted in the infield and they put me in center field.

I was still very inexperienced. But I made the Jersey City team.

Called up to the Major League’s

The Giants thought I’d be a third baseman when they called me up near the end of the ’46 season. They were playing the Cardinals, who were fighting the Dodgers for the pennant.

The manager, Mel Ott, told me it wouldn’t be fair to play a rookie against them. “Just sit and watch Whitey Kurowski play third base,” he said.

I remember Ernie Lombardi sitting on the bench with his pancake catcher’s mitt under his arm, his shoes untied. Ott would walk down to him to pinch hit.

He’d nonchalantly tie his shoes, walk to the bat rack, take a bat, maybe take one swing, and go up to hit. Most guys would have to loosen up, take some practice swings. Not old Schnozz.

In 1947 Giants pitcher Hal Schumacher had retired and gone to work for Adirondack Bats. In the spring he came into the locker room with a bunch of bats and we used them.

Walker Cooper put some little nails in his bats and they didn’t catch him for a while. We set a home run record with 221. We got rings with “221” on them.

They talk about cheap home runs down the short foul lines in the Polo Grounds; I hit a few of those. But as a left-center hitter, I lost a lot of 400-foot fly balls in the Polo Grounds that would have been home runs in most parks.

In the first playoff game in 1951 at Ebbets Field, the home run I hit off Branca was left-center, right over the 375-foot sign. That would have been a pop fly in the Polo Grounds.

I got into a slump in ’48 and everybody and his uncle is telling you how to hit. Two I listened to were Mel Ott and Hank Greenberg. Slumps start in your head. It’s like trying to make a three-foot putt in golf.

Your mind has a lot to do with how you approach things.

Changing things at the plate

I changed batting stances. Feet wide apart, bat held back, copying Joe DiMaggio, they said. But I didn’t know from Joe DiMaggio.

I just had my hands entirely different from the year before, and I don’t know how these things come about.

It was a shock when Leo Durocher came over to manage the Giants in 1948. Mel Ott was a real gentleman and Leo was a fiery noisemaker.

He was aggressive, smart, could be obnoxious. But who’s perfect?

In his first meeting he said, “Boys, let’s just forget everything that’s gone on in the past.

What counts now” -- he rubbed his hand across his uniform shirt – “is Giants. We all go down the road together or we go different ways and don’t win.”

We got used to him in a hurry.

Rivalry with the Brooklyn Dodgers

Like the Giants’ fans, I used those words: “We hate the Dodgers.” But we didn’t know them as people, we knew them as players.

I always thought of Branca with those big baggy pants and as a pitcher he didn’t like us and we didn’t like him.

They were the enemy and that’s the way it was. In Ebbets Field the locker rooms were right next to each other and we had a common runway so you had to pass guys on the other team between the dugout and locker room.

I never talked to them, except to say hello to Gil Hodges because he was such a respected guy.

The walls between the locker rooms were thin. When they beat us, we could hear them banging on the walls, singing, “Roll out the barrel, we got the Giants on the run.”

[The Dodgers had a 13-game lead on the morning of August 12, 1951 They were 26-22 and the Giants 37-7 the rest of the way and finished in a tie.]

Leo would tell us, “Don’t get them mad. When the time comes, kick their teeth in.”

One day at Ebbets Field they had two on, two out, first base open. Leo plays the percentages – intentional walk. Carl Furillo is up. Hits the first pitch for a grand slam.

Ebbets Field is so small you can talk between the dugouts. Carl goes in and hollers, “Hey, Leo, how did you like that?”

That got us mad.

Tense moments throughout the ‘51 season

I remember once facing Don Newcombe with Monte Irvin on third, losing 1-0 about the sixth inning and Newcombe getting two strikes on me and now I’m fighting for my life and I’d never felt that way before and I had to get that run in and the next pitch is right under my chin and I swung at it and hit it right over the Dodger dugout.

I couldn’t leave that guy on third. The next pitch was probably outside a couple inches. I just got my bat on it and hit a long fly ball. I remember really like fighting for my life that one time at bat.

The last week of the season the Dodgers were in Boston, which was loaded with former Giants – Buddy Kerr, Sid Gordon, Walker Cooper, Willard Marshall.

The Braves were going nowhere. In the next to last game of the series, the Dodgers led, 13-3, in the eighth inning and Jackie Robinson stole home. He’s on the bench, laughing, making all kinds of gestures.

That got the Braves mad. Walker Cooper coulda wrung his neck. The next day the Braves were out to show them, tried a little harder, wound up winning three of the four games.

The week before the season ended we couldn’t afford to lose a game. We finished with two games in Boston. I was playing third base.

The last game, when Willard Marshall came up with the tying run on second, my heart was in my mouth. I hadn’t felt that way the week before.

With the pressure you get more determined to do whatever you can do. Fortunately, Willard hit a fly ball to left

There was always a lot of press ballyhoo and big crowds whenever the Dodgers were at the Polo Grounds for a weekend series.

Leo would tell us, “Let’s just play our ball game. But” -- there was always a “but” – “But as soon as one of their pitchers comes too close to one of our hitters’ chin, I want two for one.” Typical Durocher.

A deciding game between two fierce rivals

[After splitting the first two playoff games, the deciding game was played at the Polo Grounds. The Dodgers, behind Don Newcombe, had a 4-1 lead after 8 ½ innings.]

When we came in for the bottom of the ninth, I was totally dejected and threw my glove down on the floor.

I thought we were just good enough to come this far, but not good enough to take that last step. I knew I was the fifth hitter.

I didn’t expect to get a chance to bat. Newcombe had walked right through us in the eighth.

[With one out and two on, Whitey Lockman doubled in a run. It was now 4-2 with men on second and third. Don Mueller hurt his ankle sliding into third, holding up the game. Thomson was the next batter.]

It was a once-in-a-lifetime situation. Don was a good guy, good ballplayer, he’s lying there really hurting.

You could rationalize that Don hurting his leg stopped the game, broke the tension, got my mind off the game. I think that coulda been a factor.

They carried him off the field and now all of a sudden I’m thinking I gotta get back to bat, there’s a ball game going on here.

I didn’t pay attention to the crowd. I didn’t even know they had changed pitchers.

So now here I head toward home plate and I remember Leo putting his arm around my neck, saying, “If you ever hit one, hit one now.”

I thought, “You’re out of your mind.” I didn’t even look at him, certainly didn’t answer him.

And then, fundamentals seem to take over. I try to rationalize this -- the only thing I can do to make sense. You’re supposed to be a professional.

You can go up there in a tough spot, be a little afraid of it. But over your career you face situations where you maybe feel a little tighter than others.

I just started talking to myself: “Wait and watch. Get up and give yourself a chance to hit, you S O B.” I’m swearing at myself all the way.

It seemed like a long walk from third base to home plate. “Wait and watch. Give yourself a chance to hit. Do a good job, you S O B. Wait and watch.” The idea being, don’t get overanxious.

Keep your weight back. Give yourself a chance. That’s all you can do, and let the good lord do the rest.

It wasn’t until I got to home plate that I realized they had changed pitchers. So now I get in the batters’ box. I took the first pitch right through the middle of the plate.

I remember Larry Jansen saying later, “Jesus Christ, we wanted to kill you when you took the first one right down the middle.”

It wasn’t a matter of being nervous, just total concentration. It’s a daze or whatever term you want to use, but you’re just totally concentrating.

Nothing’s going on around you except this thing in front of you. I’d never been in a situation like that where it was that critical.

I wasn’t fighting for my life, but I was totally concentrating, waiting and watching. And now I’m in my crouch and he winds up and I remember just getting a glimpse of it – I use that term getting a glimpse of it.

Maybe I didn’t see it all the way to the bat. It’s coming high inside. If it’s inside, your hands better get out in front of it. It was a bad ball but obviously it wasn’t that bad.

For days afterward, wherever I went people would tell me where they were at that moment. I still get letters from people telling me where they were.

After the Game

I was still living with my mother on Staten Island. I wasn’t one for the nightlife. After the game I went home.

After what we’d been through, playing the Yankees in the World Series was like playing a sandlot game. I never felt more relaxed in my life.

I couldn’t believe how hard Allie Reynolds threw. Monte Irvin was on second base with two outs and I hit a single so hard to left field, Irvin couldn’t even score.

[Thomson was traded by the Giants in 1954 before they went to the World Series, and by the Braves in ’57 before they wound up in the Series. He retired from baseball in July 1960.]

I walked away from baseball and didn’t miss it. I began a new, more normal life. I learned the meaning of work, and became aware of the value of time and money. Baseball was play.

Now I experienced a working life, rode trains and subways, setting out each day with a goal to accomplish, things I never felt playing baseball.

As a ballplayer, you are self-centred: how am I doing, how am I hitting? It’s always I, I, I.

It was satisfying to become aware of others around you and their needs. I worked in sales for paper and carton manufacturers until I retired.

I remember Mel Ott telling me, “Bobby, stay with it as long as you can. You never know what’s going to happen after baseball.”

I didn’t feel that way. I feel I’ve grown a little bit.