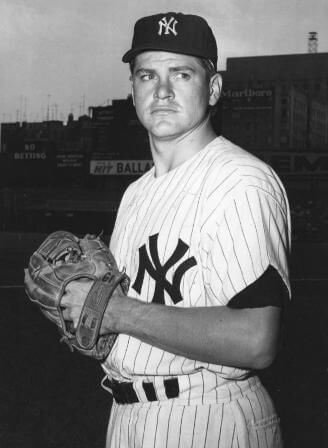

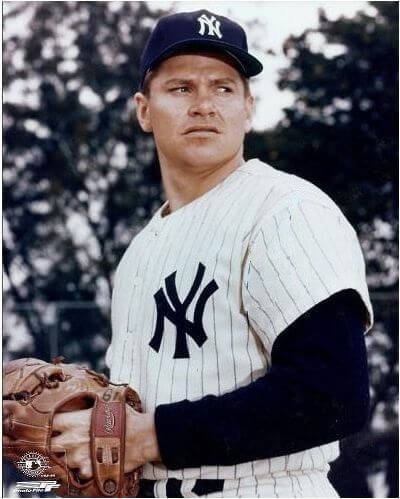

Bob Turley: The Original No-Windup Pitcher

Bob Turley: A Natural in Pinstripes

A big right-handed high fastball pitcher for the St. Louis Browns, Baltimore Orioles, Yankees, Los Angeles Angels and Red Sox (1953-1963), Bob Turley pitched in five World Series with the Yankees.

His best year was 1958: 21-7, Major League Cy Young Award, World Series MVP -- working in four games with a 2-1 record.

Turley was living in a 13,000 sq ft mansion at the south tip of Marco Island in southwest Florida when we visited him in March 1984. - Norman L. Macht

A column of stately royal palms lined the driveway. A wall-sized plate glass window looked out on the Gulf of Mexico. A small yacht was moored at a dock.

His Cy Young Award plaque was mounted on the wall of a huge open area in the house.

Bob Turley tells his own life story

I was born in a small town, Troy, Illinois, about 20 miles outside St. Louis, and grew up in East St. Louis.

My high school coach, a bird dog for the Browns, arranged a tryout for me at Sportsman’s Park.

The night I graduated from high school in 1948, I signed for $1,200 -- $600 bonus and the rest salary. They sent me to Belleville in the Illinois State League, close enough so I lived at home.

I was used to pitching four or five games a week – never had a sore arm. But for about two weeks I pitched nothing but batting practice.

First outing for the Browns

One day the Browns called and asked why I wasn’t pitching. They wanted me to start that night. I had just thrown BP for thirty minutes and was running in the outfield when they told me I was pitching that night.

So I pitched against West Frankford, beat them 3-1, and struck out 10 or 11.

The next day they fired the manager. I finished 9-3.

The 1949 Season

In 1949 I went to spring training in Pine Bluff, Arkansas.

The Browns had 26 farm teams at that time, and all of them except the AA and AAA teams trained at this old army base must have been about 500 of us of all ages.

I was 18 and there were some guys in their thirties. We slept in the barracks.

During the summer they grew corn in the field there. In the spring they plowed.

They lined us up and we walked across the field picking up corn stalks and rocks.

Then they used machines to smooth it out and put down four baseball fields. We did our running alongside the air strip.

They were paying me the same $200 a month I’d made in ’48, and sent me to Aberdeen, South Dakota, in the Class C Northern League. Long bus trips.

We played a July 4 doubleheader at home, about 104 degrees, got on the bus, drove all night and the next day to Duluth, Minnesota, got off the bus and there were snow flurries.

I was 23-5, never taken out of a game starting or relieving, and won two playoff games.

After the season we played an exhibition game against a local semi-pro team. In the first five innings I struck out everybody. One inning we had nobody behind me on the field except the first baseman.

Moving into the 1950s

I trained with the Browns in Burbank in 1950. They sent me to San Antonio. I pitched two games, lost 1-0 and 2-1, and they sent me down to Class A Wichita in the Western League. Never figured that one out.

That’s where I ran into Don Larsen. He was 20; I was 19. Joe Schultz was the manager.

He had more to do with my career than anybody because he was an old catcher and I learned about how to play the game from the pitcher’s point of view.

The next year I was 21-7 at San Antonio and was called up by the Browns, pitched one game and got beat by the White Sox.

I was about to be drafted into the army, so I went back to Texas and enlisted. I knew the general there and he wanted me to pitch on his base team.

All I did was play baseball for two years and got back to the Browns for the last month or so in 1952.

1953 and fresh from time in the Army

The ’53 Browns were a lot of older guys near the end of their careers. Marty Marion was the manager.

I remember sitting next to him when a sportswriter asked him, “How come you don’t play anymore?” He said, “I ain’t going out there and embarrassing myself with these bums.”

One of the catchers was Clint Courtney, who fired the ball back to the pitcher. I think if he threw it back easy, it would be erratic, all over the place.

When Duane Pillette was pitching and nobody was on base, he would step aside and let Courtney’s throw go out to center field.

I knew a lot of catchers who, if there were men on base, couldn’t throw the ball back to the pitcher. It’s a mental thing, just like a pitcher’s control.

Baseball icon Bob Turley

Satchel Paige was there. He was always chewing gum and he’d warm up by taking the gum wrapper and laying it down and throwing over it. He had a rocker in the bullpen and he’d fall asleep out there during the game.

I made $6,000. Even with the [54-100] Browns, players were paid for helping win games, not just the stars. Like hitting behind the runner, stuff that they don’t keep stats on, or a reliever who comes in and stops a rally.

How many times do you see a man on second base and the batter hits in front of him, not behind him. Things like that make a difference in winning.

Hit it on the ground to the right side, move him over, and another ground ball can score a run. The attitude was, “Gotta get the run in.”

It’s the .240-.250 hitter who’s asked to sacrifice for the good of the team. The front office has to recognize that and pay them accordingly.

Moving to Baltimore

The move to Baltimore in 1954 was exciting. In St. Louis, we had maybe 800 people at a game. But we found out very quickly we were the same team, just in different uniforms.

Jimmy Dykes was the manager. Dykes loved the press, being the center of attention.

He did more talking to the press than the players. You’d find out more about yourself from the papers than the manager.

There were all kinds of prizes you could win, trips and things. First home run would win a diamond ring, etc.

We had a meeting and somebody suggested putting all the prizes together and turning them into cash and dividing it because some guys had more chance of winning something than others.

One player said, “If I win something and you think I’m going to divide it with you guys, you’re crazy.” He hit the home run to win the ring.

I won a Cadillac and a trip to Japan. We couldn’t split up the Cadillac, but we took the cash for the trip and divided it, about $1,000 each.

Tim Cohane from Look magazine wanted to see how hard I threw. The Orioles agreed to it, but it had to be after I pitched.

So one day I went to Aberdeen Proving Grounds. They put a machine on home plate for me to throw through. I threw 98-point something mph and that’s where the nickname Bullet Bob came from.

They timed it crossing home plate. Now they time it halfway to the plate. On that basis a lot of guys I knew could top 100.

Getting traded to the New York Yankees

I stayed in Baltimore that winter. One night I was watching Steve Allen on the Tonight Show on TV and all of a sudden my picture flashed on the screen.

“Bob Turley traded to the New York Yankees.” I was so excited it was unbelievable. [Turley, Don Larsen and five other Orioles were traded to New York for 10 players.]

The phone was ringing. Fans said they were sorry to see me go. I was kind to them, but in Baltimore they had averaged maybe one or two runs a game.

In New York they averaged maybe six runs a game.

My first spring training with the Yankees, I walk in and there were a couple drinks in my locker. Mickey Mantle walked over and said, “I’m so glad you’re here, another guy I can’t hit.”

Life with the Yankees

Casey Stengel didn’t have meetings to go over the hitters. Going over how to pitch to hitters didn’t help much anyhow.

The manager or pitching coach would say, “Don’t throw a high fastball to this guy” or “Throw curves to that one low and away.”

I lived on my high fastball. What was I supposed to do? If I could control a curve low and away, I’d be winning 40 games a year.

The outfielders wanted to know how you were pitching to a hitter. The infield would relay the signs to the outfield.

Before a World Series game, Stengel might talk about hitters but it would be like, “Now this guy is a low ball hitter . . . likes it low and away,” and then it would be “Heinie Manush [or some other oldtime player] couldn’t hit an outside pitch” or something like that.

The 1956 World Series

Toward the end of the ’56 season, we’re getting ready to play the Dodgers in the World Series.

And the pitching coach, Jim Turner, suggested to Don Larsen that he try pitching without a windup because teams were stealing his pitches.

Then Turner says to me, “I want you to do the same thing but for a different reason. Your windup is no good to you and you always lack control.”

The day after Larsen’s perfect game in the ’56 Series, I pitched the best game of my major league career [a 4-hit, 11-strikeout, 8 walks 10-inning 1-0 loss] in that bandbox Ebbets Field, but nobody remembers my game. Enos Slaughter lost three balls in left field.

In the tenth with two on and two out, Jackie Robinson hit it real hard to left. All Slaughter had to do was stand there. He came charging in; the ball went over his head.

Larsen went back to the over-the-head windup. I stayed with the no windup, got criticized, booed, and written up: You’re going to ruin your arm.

The benefits of the no-wind-up pitch

But it became very easy for me; I didn’t have to get in a rocking position. With better control, I didn’t have to try to strike everybody out.

I could try to get them to hit my pitch. I was able to switch the ball in my hands. I could switch to a sinker and get a double-play ball. It made me able to do what pitchers should do.

Before that my high fastball produced fly balls, not double play grounders.

Now they all do it.

I’m pitching in Washington one day, fifth inning leading 3-0, 2 out. Need one more out to be eligible for the win – and wins is what we got paid on.

A left-hand batter hit a ball over the shortstop’s head. Only man on base. I look over and here’s Stengel coming out of the dugout waving his hand for a pitcher to come in from the bullpen.

I thought, “What the hell is going on here?”

He came out to the mound, didn’t talk to me. I don’t swear a lot. I called him every dirty name I could think of, following him around the mound; he kept walking away from me.

I went in the clubhouse. I was so mad I tore my uniform off and was trying to flush it down the toilet. For about a month Stengel avoided me.

One day we’re on a train and I’m in my roomette reading a book and he stopped by and said, “Now that you’ve quieted down, I’m going to tell you why I took you out of that game. You weren’t striking anybody out.”

I said, “Casey, get out of here.” I had been pitching a hell of a game. What can you say?

[In Game 2 of the 1958 World Series against Milwaukee, the Braves scored 7 runs in the first inning off Turley. He came back to shut them out in Game 5. How did he explain that?]

In that second game my stuff was good but maybe the ball wasn’t moving, maybe I was throwing the same speed. I don’t know.

Any pitcher will tell you out of four games you pitch, one you’ll have exceptional stuff. Your object is to win two out of three you’re pitching.

I had many times when I’d go out there and just have extraordinary stuff, and times when I felt so good it was unbelievable.

Turley on his Yankee’s teammates

Yogi Berra was a great all-around player. Smart, not excitable. Learned how to get rid of the ball and throw guys out.

Elston Howard was more into the emotional side of it with a pitcher. He’d come out and talk to you, encourage you. Both were great catchers.

Ralph Houk was a players’ manager. He kept everybody excited, and happy, talked to you, made you feel like you were part of the team like you were doing it, not him. Appreciated what you were doing.

I had the ability to call some pitchers’ pitches. Mickey Mantle and Gil McDougald especially wanted the tips. Mickey said, “You’re right 85-90 percent of the time.”

I’d go into the TV room to look at pitchers’ motions to see what I could pick up. I might tell Mickey, “Watch his foot.

When he’s going to throw a screwball, he moved his foot to the other end of the rubber.”

Analysing other pitchers

Billy Pierce always wore a long heavy sweatshirt. When he went into his glove to throw a fastball, his sleeve would go down to his wrist.

For a curve, he would go deeper into his glove and his sleeve would be off his wrist. So I told Mickey that.

All pitchers try to work on their stuff and be consistent in what they do.

Early Wynn, with somebody on base, if he was going to throw a knuckleball he’d do something in his stretch, a fastball he’d come up even with his chin, a curve he’d be up around his forehead.

Or I’d I tell them, “Watch the glove. It spreads more when he’s gripping a curve than a fastball.” I picked up on things like that.

When you throw a curve, you shorten your stride. Pitchers would alter their windup a little from fastball to curve. With the no windup, it’s more difficult to pick up those things.

Calling pitches from the stands

When I was on the DL, they’d buy me a seat in the stands and I’d call pitches from there.

Whistle to them to give them the signs.

I could read our pitchers, too. I called Whitey Ford’s signs all the time. He called his own games, giving the signs to Yogi.

If he bent over and shook his head, it was a fastball. If he stood up, it was the reverse of that.

I asked him once, “How long you been calling your own games?” He looked at me. “What do you mean?” When I was traded, they changed their signs.

The hardest thing is to get a pitcher to realize what they are doing. They get into a routine and don’t realize it.

The 1960s

I never had a bad arm, but it was sore during the 1960 Series. I didn’t pitch much in ’61 – we had a good pitching staff.

At the end of the ’61 Series I had it operated on to remove the bone chips. In ’62 we had another good staff and I didn’t get to pitch much.

The older you get, the more you have to pitch, especially for me to maintain my control. Your muscles don’t come back as fast. You have to do more throwing, more working out.

Your work habits are more than all the young guys put together. Like Ryan. Like Clemens. We didn’t know anything about icing your arm after pitching a game.

We used hot water in the shower. We never used the whirlpool. We had one trainer, not six or seven. I could still throw pretty hard but I was just not into it.

Mantle and Maris

Some of the Yankees had an active nightlife. Mickey was one of them. But he was like Babe Ruth: when they put that uniform on, that overcame anything they did the night before.

I’ve seen some guys miss a game because of the nightlife, but not Mickey.

He loved to play and win. In 1961 Mickey hurt his shoulder and hit few home runs in September. But he still wanted to play even though he could barely swing a bat.

He never complained, never moaned. He liked to kid around, always laughing. He loved to warm up with rookies – he could throw a knuckleball and he’d throw that thing to them and laugh when it tied them up.

Roger Maris was the opposite, a good guy but not outgoing, a family man. It’s true that the guys were rooting more for Mickey to break Ruth’s record than Maris.

But Roger was probably the best right fielder the Yankees ever had, played way in and could go back on a ball. Very fast.

Moving to the Los Angeles Angels

Then I was traded to the Los Angeles Angels. The only game I can remember not walking anybody was with the Angels.

And I pitched a one-hitter against Chicago. We called manager Bill Rigney Mr. Hook. Every time he took me out of a game, everybody on base scored off whoever came in.

One day about the fifth inning he came out to the mound. Bases loaded. I said, “Look, if you check it out, every time you bring somebody in, everybody scores.

I can’t do any worse than that. Pitching is very simple with nobody on base. I’m good with men on base if you’ll just let me get ‘em out.”

All this is on the mound. He looked at me, said, “Okay,” went back and I struck out the next three guys.

Umpires have different strike zones. They are human beings and they take a lot and they hear it. Ed Runge was a pitcher’s umpire.

But if you showed him up, forget it. I pitched 24 shutouts and I bet half of them were with Runge behind the plate. Hitters knew it too.

With Runge, they wouldn’t take pitches. He’d call them out on pitches that far outside. The Yankees would use me when he was behind the plate. I don’t think I ever lost a game with him umpiring.

Ed Hurley for some reason didn’t like me. I don’t care what I did, he couldn’t call a strike. One day in Chicago I was throwing the ball right down the middle of the plate.

He’s calling ball…ball…ball. They had to take me out. Guys in the dugout were yelling at him. He thought it was me.

One day he came out to the mound and said, “Don’t worry. I’m not going to throw you out of the game. I’m going to let you pitch yourself out of the game.”

I wrote a letter to the league president; nothing came of it.

[Turley was the Yankees’ player rep in 1958.]

Fighting for ball players salaries

I remember when J. Norman Lewis was our union head and we proposed to the owners that they allocate 20 percent of all their baseball income to players’ salaries.

I’ve never seen grown men act like we just killed them.

I remember Buzzy Bavasi saying, “You mean to tell me, we came in last and just because we drew four million and made a lot of money, we gotta pay you guys 20 percent of it?”

Tom Yawkey’s on the other side and he says, “Here’s my books. I’m already paying that now.”

Today they’d be the happiest people in the world if they’d signed that contract.

Billy Crystal

I was at Mickey Mantle’s funeral. When the services were over, the comedian Billy Crystal came rushing over and shook my hand.

He said, “I’ve been waiting a long time to talk to you. When I was a little boy my mother used to take me to the Yankee games. I’d try to get autographs and never could.

One day you came out and were walking across the grass and my mother asked you if you’d sign and you said you’d be happy to.

Then my mother asked if she could take a picture with me and you said you’d be happy to.” I sat him on my knee for the picture. He said, “That’s my favorite picture. It sits on my desk.” Made me feel good.