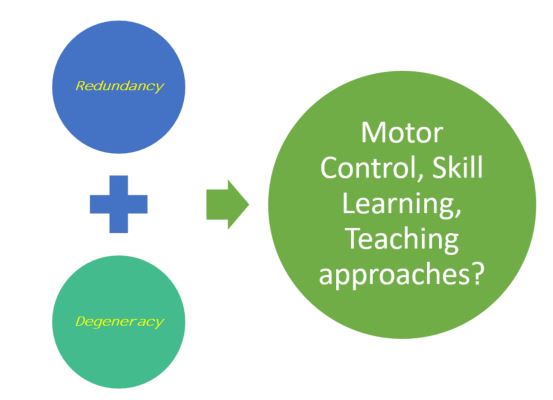

I find these two words, Redundancy and Degeneracy, keep cropping up in my mind as I explore and delve further into how people adapt to the world they live in to hopefully get a better idea of learning. The words sort of represent a short cut for me to understand much of what is sometimes said about skill acquisition and learning in PE. Probably without giving justice to a proper definition, Redundancy refers to the fail-safes we have in systems to prevent too much reliance on any one process. This is vital in artificial systems and seems to be likewise in us too as complex systems. Degeneracy is a characteristic description borrowed from other sciences and suggest that different structures within a system can perform the same function or yield the same output.

These pair of words may sound simplistic and maybe even having negative literal connotations at first, especially if you have never encountered it with relation to learning and probably off-putting to someone who wants to teach better and got no appetite for seemingly obscure concepts. To me, these words points to the reason for thriving and successful ecological (living things and PE for us) and artificial systems (the wonderful technology out there). I do not claim to understand it fully but I realised my impression of these words are heightened continuously as I explore more of why learners do what they do. In an analogous way, I feel that we also need to build in Redundancy and Degeneracy within our approaches to teaching.

So recently, I did the usual, after a long while, and type out my topics of interest (i.e. ecological, physical education) into a journal search site and came across a paper by Rudd ret al, An ecological dynamics conceptualisation of physical ‘education’: Where we have been and where we could go next. (Rudd, Woods, Correira, Seifert, & Davids, 2021). It was a paper published in a respected Physical Education (PE) practise journal, Association for Physical Education (AfPE) of the United Kingdom (UK). I mentioned the journal to emphasise the mainstream acceptance to wanting to explore a perspective of PE that might be uncomfortable. This paper explore the ecological perspective to the complexity existence that skills learning takes place in, i.e. why and how movement emerges. This is perhaps opposed to the more palatable perspective of skills learning as solely mechanical and existing in a ‘simple’ environment of learner and teacher, i.e. how movement is created. This paper identifies the scientific areas of ecological psychology, dynamical system theory, complexity sciences and evolutionary biology as contributing knowledge in developing a theoretical scaffold, i.e. ecological dynamics, to understanding the phenomenon of emerging actions, grounded in comprehensive research. In easy to understand terms for me, it can be about education through the physical interacting with the world, when considering implications to PE.

Why this paper appeals to me at this point of my own professional journey? It is because it summarises in an understandable way of where we potentially need to explore much more of, as we ourselves expand on allowing our learners to explore their potential. This further exploration as teachers is nothing new and something we seem to always endeavour to in paper exercises but always not having the time to in reality. This Rudd paper (no pun intended) is worth spending some time on as a reflective way to look at what we have been doing and how to improve. However, as much satisfaction I get from this paper, I also realised the possibility of colleagues reading it going on defensive mode that is quite the usual in much academic sharing situations where there is a hint of ‘either this or that’ implication.

It was good to be led to very interesting summaries of our reliance on Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) (internal, external and germane cognitive load) and Fitts and Posner’s (cognitive, associative and automaticity stages) skill acquisition model. This has been a big influence on how we have been practise teaching whether we know it or not, at least for me it still is to some extent. Basically, a lot of the responsibility for handling knowledge, and therefore skill acquisition, is placed on how our brains, the anatomical structure within our skull, seemingly manages it. In PE, there is even the added conundrum where we as teachers may work on this cognitivist view while our fellow stakeholders sees PE as strictly a physical only endeavour to occupy students when their ‘cognitive load’ reaches breaking point from the class-based subjects.

What this paper examines is a re-envisioning of how we can involve the learner in a teaching situation, to re-balance better the traditional way of creating learning that is based mainly on what is happening within the learner. This re-balancing also needs to involve the world in which the learner is attempting to be better in. It is more a journey taken together with the teacher through carefully thought out lesson designs that consider task-learner-environment.

The concept of non-linear development comes in. It suggest the not so direct path that a learner takes in acquiring skills. While the planning and implementation strategy of a teaching approach is orderly and perhaps even be considered linear, the development of the learner within that structure may have to cope with non-linearity within the learner, between learners and all the time considering the relationship with task and environment. An example for this is when different students develop at different pace and they might not always mimic established, teacher-led techniques at their initial learning phase as their most natural progression. In addition, skills being taught means very little to the learner without focusing on a purpose that makes sense to the learner. This purpose connects to the role a task plays in creating meaning to the life of an individual, represented by a collective perspective to some extent (for practicality, we need to normalise for groups of learners at times). For example, we understand the role of play creating joy. How do we illicit the same feeling joy through play in crafting a purposeful task, if our intent in the learning process is as such?

We are also aware that understanding a concept creates the motivation to want to ‘learn’ more and thus will do well to offer it in our lesson designs. The ecological approached espoused in the papers, above and below, try to hypothesise the way we create movement, emerging solutions, as a result of needing to meet the requirements of what is meaningful to our learners.

I believe that not considering all the intricacies mentioned will still develop the learner but it happens in spite of our attempts in encouraging learning. After all, learning is an adaptation and overcoming mechanism. The difference is the effectiveness of deliberate facilitation of learners’ adaptation and learning (a causal-effect approach) as compared to one that occurs almost incidentally but credited to our practises (correlational).

Some of the authors above, together with Rob Gray – a very active practitioner/academic in perception-action work (ecological dynamics approach to skill acquisition), also published another paper that borrowed from the Social Anthropology based concept of Enskilment from Ingold (as cited in the paper). This paper suggest an Ecological-Anthropological Worldview of Skill, Learning and Education in Sport (Woods, Rudd, Gray, & Davids, 2021). Enskilment cuts through the usual division of mind, body and the world we operate in. The three components of Enskilment are Taskcape (the task environment and its intricacies), Wayfinding (discovery via the whole person interacting with context) and Guided Attention (the expert/teacher guiding). The two papers above have a similar message, as similar as two different scientific perspectives can be, written by mainly the same people. The former paper considers processes within the body to make sense of context interactions while the latter starts off with looking at interactions first to make sense.

Both papers may not be so well received by practitioners (teachers on the ground) not used to the related domains of studies cited to bring out the ideas, even though I feel the ‘story-telling’ approach of Social Anthology connects to us better. This brings to my mind the shame of having to miss so much valuable insights if we do not take risk with our professional development broadening.

Will looking at a behaviour, adaptation, learning, etc. with a wider view something we are comfortable with as practitioners? In the spirit of degeneracy, can we accept that being open to the complexity of even the processes that govern complex systems will help in our teaching mission. Not specifically looking for alternative structures but rather parallel structures working in tandem to accomplish purposeful movement. Perhaps with such thinking, we can better build in redundancies into our teaching, to meet ever changing learner needs within stable and unstable context.

Readings

Rudd, J. R., Woods, C., Correira, V., Seifert, L., & Davids, K. (2021). An ecological dynamics conceptualisation of physical ‘education’: Where we have been and where we could go next. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 293 -306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2021.1886271

Woods, C. T., Rudd, J., Gray, R., & Davids, K. (2021). Enskilment: an Ecological-Anthropological Worldview of Skill, Learning and Education in Sport. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00326-6